Why Academics Are Susceptible to Ideologies and Cult-Like Movements: A Philosophical and Socio-Psychological Analysis

Introduction

Academics, trained in rigorous inquiry and evidence-based reasoning, might seem unlikely to embrace unproven ideologies or cult-like frameworks. Yet, history and research reveal a paradoxical vulnerability. This susceptibility arises not from intellectual deficiency but from intertwined philosophical, psychological, and sociological factors.

- Philosophically, it stems from epistemological biases where rational tools justify irrational beliefs.

- Psychologically, cognitive heuristics and the allure of complexity play roles.

- Sociologically, institutional dynamics foster groupthink.

Using “gender ideology”, a term critiquing certain views on gender as “socially constructed” yet rightly criticised for lacking any scientific grounding and ties to controversial figures, as an example, this article explores these dynamics. Balanced perspectives will be presented: it’s rooted in pseudoscience and paedophile-apologist writings, while proponents call it a legitimate deconstruction of binary norms grounded in social sciences (aka utter nonsense and drivel).

Relevant studies and quotes substantiate the points, highlighting how ideologies gain traction in academia despite weak empirical foundations.

Epistemological Overconfidence and Motivated Reasoning

Philosophically, academics proudly align themselves with the pillars of rationalism and empiricism, Descartes’ methodical doubt, where one strips away every assumption to rebuild knowledge from unquestionable foundations, or Popper’s falsifiability criterion, insisting that genuine scientific claims must be open to refutation through evidence. These frameworks are meant to cultivate intellectual humility, rigorous scepticism, and a commitment to truth over ego. In reality, however, this very training often cultivates the opposite: an epistemological arrogance that inflates intelligence into a shield against self-correction. Rather than mitigating bias, high cognitive ability amplifies it, enabling people to spin ever-more-convincing webs of justification around preconceived notions. In other words, this training can breed overconfidence, where intelligence amplifies bias rather than mitigating it.

Michael Shermer, nails this dynamic in, Why People Believe Weird Things, argues: “Smart people believe weird things because they are skilled at defending beliefs they arrived at for non-smart reasons.”

Why people believe weird things | Michael Shermer

- https://www.ted.com/talks/michael_shermer_why_people_believe_weird_things

- https://www.ted.com/speakers/michael_shermer

Smart people believe weird things because they are exceptionally adept at defending beliefs they adopted for non-smart reasons, tribal loyalty, emotional comfort, moral signalling, or ideological conformity. Gender ideology exemplifies this perfectly. From my standpoint, it’s a bizarre, reality-denying construct that ignores biological sex as binary and foundational, yet brilliant academics champion it fervently. They didn’t arrive at it through cold, empirical scrutiny of genetics, endocrinology, or evolutionary psychology; they latched on for social, political, or virtue-driven motives. Once hooked, their superior reasoning skills kick in to fortify the position against all challengers. This “motivated reasoning” involves seeking confirmatory evidence while dismissing contradictions, often aligning with political identities.

Studies support this: A meta-analysis of 63 studies found intelligent people resist religious dogma due to analytic thinking but may rationalise other biases. It revealed intelligent individuals, who often use their sharp minds to resist dogmatic beliefs in areas like religion, use the same tools, as they get redeployed to rationalise secular or ideological biases with equal vigour. Analytic prowess doesn’t guarantee objectivity; it equips people to be more persuasive in their self-deception.

In academia, this plays out in a heavily skewed environment where left-leaning perspectives dominate, surveys from recent years, including those at elite institutions like Harvard, show around 60% or more of faculty identifying as liberal or very liberal, with conservatives often in the low single digits or teens.

https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2021/4/9/disappearance-conservative-faculty/

This imbalance isn’t neutral; it creates powerful echo chambers where dissenting views are rare, stigmatised, or career-limiting. Ideologies like postmodernism flourish here, with thinkers like Foucault emphasising that knowledge is inseparable from power structures, effectively relativising objective truth to whoever holds cultural dominance. In such spaces, gender ideology isn’t rigorously tested, it’s shielded by the assumption that questioning it equates to oppression. Intelligence doesn’t inoculate against this; it supercharges elaborate rationalisations, turning flawed premises into impenetrable theoretical fortresses.

A telling analogy comes from observations in other contentious debates: some highly knowledgeable sceptics on issues like climate change possess deeper factual command than average believers, yet deploy that expertise selectively to reinforce denial rather than challenge it. Chris Hayes notes that smart climate deniers know more about the topic than acceptors, using knowledge to deny it. The mechanism is identical, motivated reasoning turns knowledge into ammunition for preconceptions. In gender ideology, this manifests starkly through its intellectual lineage.

In gender ideology, critics trace origins to John Money, who coined “gender role” via unethical experiments (e.g., the Reimer case, involving forced reassignment and later suicides). Money defended “affectional paedophilia.” Alfred Kinsey’s influence compounds this ethical shadow, with his reports incorporating timed accounts of child “sexual responses” from abusers, presented as scientific data without intervention to stop ongoing crimes. Proponents of gender ideology sidestep these origins, instead championing social constructionist views, most famously Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity. Butler argues that gender isn’t a stable, innate essence tied to biology but a repeated performance, acts, gestures, and behaviours shaped by cultural norms that create the illusion of a fixed identity. Through subversion (like drag or non-conforming acts), these norms can be exposed as contingent and destabilised, freeing individuals from essentialist constraints. This is hailed as liberating, dismantling rigid binaries and empowering fluid self-expression.

This is the height of epistemological overconfidence: academics, armed with sophisticated theory, rationalise away the foundational ethical lapses in Money’s and Kinsey’s legacies because those ideas align with an anti-binary, postmodern ethos that flatters their sense of radical insight. Gender ideology endures in these circles not in spite of hubris, but because of it, brilliant minds masterfully defending fundamentally non-rational beliefs, all while convincing themselves (and others) they’re the true guardians of reason and justice.

Figure: Zealots are the most intense and often most visible members of an ideological group. They are deeply committed to the doctrine and treat ideological alignment as a central criterion for judging others, showing strong in-group love/loyalty and strong out-group disdain, contempt, or hostility.

Example: A vegan zealot who not only follows veganism strictly but looks down on, shames, or actively dislikes non-vegans (or sees them as morally inferior). In extreme cases, this quadrant can produce fanaticism, moral superiority, or even cult-like dynamics.

Psychological Vulnerabilities: Cognitive Biases and the Need for Complexity

Psychologically, humans are wired for certain shortcuts and illusions that make us prone to flawed thinking, even, or especially, when we’re intelligent. Confirmation bias leads people to favour information that supports what they already believe while downplaying or ignoring evidence against it. Magical thinking adds another layer, where individuals attribute causality to patterns or forces that aren’t there, often seeking deeper, hidden meanings in everyday phenomena.

“Intelligent people are more susceptible to pseudoscience because they crave complexity, weaving intricate narratives around weak data.”

This craving for complexity draws smart people toward elaborate, counterintuitive frameworks that feel profound and exclusive. Gender ideology fits this pattern perfectly, it’s a dense, multi-layered theory that rejects straightforward biology in favour of fluid, socially constructed identities, promising a revolutionary rethinking of human nature. From my perspective, this isn’t genuine insight; it’s intellectual indulgence. Academics and intellectuals latch onto it because it satisfies their desire for something more sophisticated than “sex is binary and adaptive,” allowing them to construct vast theoretical edifices on shaky empirical ground. The appeal lies in the illusion of depth: the more convoluted the explanation, the smarter one feels for grasping it.

Cults and cult-like movements exploit this vulnerability by providing “enlightened” systems that flatter the adherent’s sense of superiority. They offer secret knowledge or radical truths unavailable to the masses, creating a bond among the initiated who see themselves as ahead of the curve. Gender ideology exhibits similar dynamics in activist and academic circles: dissent is pathologised as bigotry or ignorance, while adherence signals moral and intellectual elevation. The group reinforces its narrative through shared language, rituals of affirmation (like pronoun declarations or DEI trainings), and ostracism of sceptics, mirroring how cults isolate members from outside perspectives.

Higher education, while effective at dispelling simplistic superstitions (like astrology or homeopathy), often intensifies polarisation on ideologically charged scientific or social issues. More years of schooling, science classes, or literacy in a field don’t necessarily lead to greater objectivity; instead, they equip people with tools to defend partisan positions more aggressively. On topics like vaccines, climate, or gender, educated individuals on opposing sides dig in deeper, using their knowledge to rationalise away inconvenient facts. This backfire effect turns expertise into a barrier to truth-seeking rather than a pathway to it.

A higher internal locus of control, believing one’s outcomes stem primarily from personal actions and choices, tends to align with more structured, hierarchical ideologies that emphasise individual responsibility and traditional norms. In contrast, those with a more external locus (attributing events to fate, society, or powerful others) may gravitate toward fluid, relativistic frameworks that downplay fixed realities. Gender ideology, with its rejection of innate sex differences in favour of personal declaration and social construction, appeals to those comfortable with external influences shaping identity, while clashing with views that see biology as a stable foundation.

https://helpfulprofessor.com/internal-locus-of-control-examples/

Academic specialisation further compounds these issues by creating silos where experts know a lot about narrow domains but lack cross-disciplinary checks on their assumptions. A psychologist steeped in social constructionism might overlook evolutionary biology; a humanities scholar versed in postmodern theory might dismiss endocrinology. This compartmentalisation reduces the chance of self-correction, allowing biases to fester unchallenged within echo chambers.

In the realm of gender ideology, critics point to cult-like features: unquestioned dogma, suppression of debate, and the elevation of flawed foundational figures. Michel Foucault’s alleged predatory behaviour toward boys in Tunisia [reports of paying young adolescents for sexual encounters in graveyards, exploiting colonial power imbalances] cast long shadows. These aren’t peripheral; they tie into broader patterns where boundary-pushing on sexuality was rationalised as liberation from repressive norms. The ideology’s defenders, however, invoke neuroscience to argue for inherent gender fluidity, pointing to studies suggesting brain structures show overlaps or variability that challenge strict binaries.

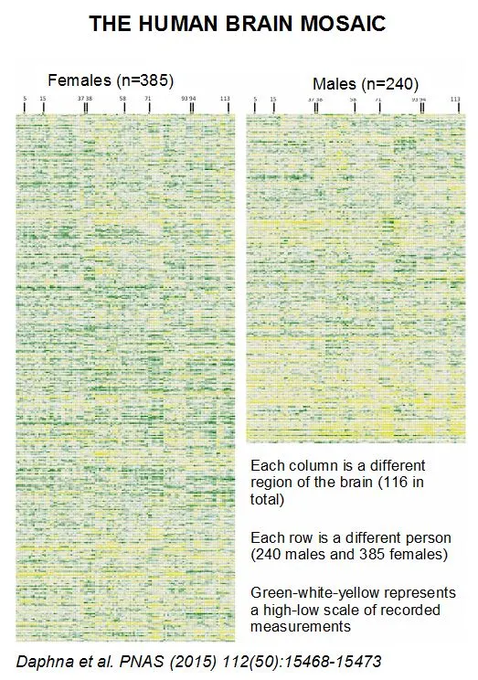

Yet these claims often overstate the case. Many neuroimaging reviews find that male-female brain differences are small on average, with massive overlap and considerable individual variation; far from proving an innate, fluid “gender identity” separate from sex. Proponents treat minimal differences as evidence of construction over biology, but this ignores how evolutionary psychology explains consistent sex differences in behaviour, cognition, and preferences as adaptive outcomes shaped by millennia of selection pressures, not mere cultural overlays. Traits like aggression patterns, mate preferences, or spatial abilities show reliable averages rooted in reproductive strategies, not arbitrary socialisation.

Academics embrace gender ideology partly because it poses a thrilling philosophical challenge to essentialism; the idea that categories like male and female have real, inherent properties. Deconstructing binaries feels intellectually edgy and morally urgent, aligning with a desire to dismantle perceived oppressions. But this comes at the cost of ignoring robust critiques: the brain sex differences, while not absolute, are meaningful and not negligible; evolutionary accounts provide parsimonious explanations without needing endless social construction layers. From reality’s view, these psychological vulnerabilities explain why such a dubious ideology gains traction among the educated elite. The need for complexity, combined with biases and group dynamics, turns weak evidence into an unassailable worldview. It’s not about truth, it’s about the ego boost of believing in something profound and subversive, even when it contradicts observable biology and leads to real-world harms like rushed medical transitions or eroded sex-based safeguards. Hubris disguises itself as enlightenment, but the foundation crumbles under scrutiny.

Sociological Dynamics: Institutional Incentives and Groupthink

Sociologically, academia often operates like a modern-day cult, enforcing conformity through mechanisms that stifle independent thought and reward blind allegiance. Drawing from Irving Janis’s concept of groupthink, we see how academic circles prioritise group harmony and cohesion above all else, leading to a suppression of dissent. In this environment, challenging the prevailing orthodoxy isn’t just discouraged; it’s seen as a threat to the collective identity. From my perspective, and the research, this is glaringly evident in the rise of gender ideology, which I view as a load of pseudointellectual nonsense masquerading as progressive thought.

Academics, swollen with hubris from their ivory tower positions, fall for it hook, line, and sinker because it allows them to feel like enlightened saviours, reshaping reality to fit their egos rather than grounding their ideas in biological or empirical truth. They convince themselves that their “nuanced” interpretations override basic facts, like the binary nature of human sexes, all while patting each other on the back for being on the “right side of history.”

Thomas Kuhn’s theory of scientific paradigms further illuminates why such flawed ideas persist in academia. Paradigms are dominant frameworks that resist change until a crisis forces a revolution, but in the humanities and social sciences; where gender ideology has taken root, there’s a glaring absence of falsifiability. Unlike hard sciences, where hypotheses can be tested and disproven through experiments, these fields rely on subjective interpretations and narratives that are immune to empirical debunking. This vacuum allows baseless ideologies to flourish unchecked, perpetuated by academics who hubristically believe their theoretical constructs are infallible. In reality, gender ideology thrives here because it’s not about truth; it’s about power and narrative control. Professors and scholars, drunk on their own intellectual arrogance, cling to these paradigms not because they’re robust, but because admitting they’re built on sand would shatter their self-image as profound thinkers. Shifts in these paradigms aren’t driven by logic or evidence but by social pressures, where the loudest voices and most conformist groups dictate the “new normal,” leaving rational sceptics in the dust.

These paradigms are often incommensurable, meaning competing worldviews can’t even be compared on equal terms because they operate under entirely different assumptions and languages. This incommensurability isn’t resolved through rational debate but through social and political manoeuvring, where the winning side marginalises the losers. In the context of gender ideology, this means that traditional views rooted in biology are dismissed as outdated or bigoted, not because they’re wrong, but because they don’t align with the socially engineered consensus. Academics’ hubris shines through here, they assume their socially constructed “truths” are superior, ignoring the messy reality that human gender isn’t a spectrum of infinite fluidity but a fundamental binary with rare disorders, that still ultimately fit into the binary. They revel in this perceived complexity, as if it elevates them, but it’s just a smokescreen for avoiding hard facts.

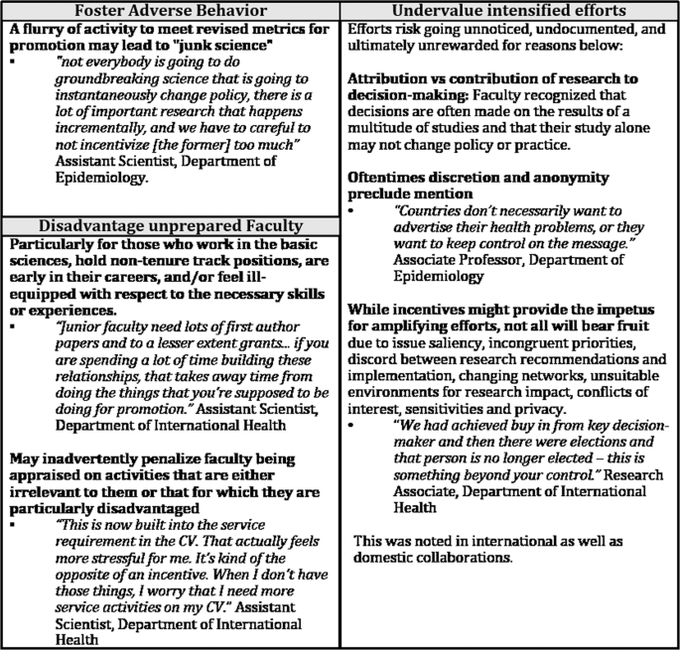

Career incentives in academia exacerbate this groupthink, heavily rewarding alignment with dominant trends like DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) mandates. Promotions, grants, and publications flow to those who echo the approved narratives, while contrarians risk professional ostracism. This creates a self-reinforcing loop where only the ideologically compliant advance, turning universities into echo chambers. From my view, this is why gender ideology has become so entrenched: it’s a career booster for the hubristic elite who see it as a way to virtue-signal and secure their status. They don’t question it because doing so would jeopardise their cushy positions, revealing their “commitment to progress” as nothing more than self-serving opportunism.

The leftist skew in academia self-perpetuates this cycle, as hiring and tenure processes favour like-minded individuals, side-lining dissenters who might introduce balance. Conservative or classical liberal voices are labelled as regressive and pushed out, ensuring the dominance of progressive dogmas. In this skewed landscape, gender ideology isn’t scrutinised; it’s celebrated as a badge of ideological purity. Academics’ hubris allows them to dismiss any opposition as ignorance, never pausing to consider that their bubble might be the real source of delusion.

Interestingly, women in the humanities may be particularly drawn to these ideologies as a form of social bonding, creating tight-knit communities where shared beliefs foster a sense of belonging and mutual validation. This isn’t empowerment; it’s conformity dressed up as sisterhood, where questioning the group could mean social exile. Hubris plays a role here too, many academics believe they’re pioneering equality, but in reality, they’re just recycling flawed ideas that undermine genuine women’s issues by conflating them with fantastical notions of gender fluidity.

Gender ideology has been institutionalised through feminist theory, tracing back to figures like Magnus Hirschfeld, whose reforms laid the groundwork for modern transgender activism.

While proponents hail this as liberation, critics rightly point out troubling connections to historical paedophile apologetics in some early writings, which casts a dark shadow over the movement’s origins. Supporters counter with references to intersex conditions as “evidence” for gender’s malleability, but this is a hubristic stretch, intersex is an outdated term, for rare medical anomalies, known as DSDs (Disorders or Differences in Sex Development), they can still be classified as male or female, proving the binary and certainly not proof that anyone can redefine their biology at will. Academics embrace this because it feeds their ego as boundary-pushers, ignoring how it distorts reality and harms vulnerable people.

Finally, the phenomenon of “woke cycles” in academia ensures that non-conformists are systematically side-lined, with cancel culture and ideological purges maintaining the status quo. Feminist critiques sometimes acknowledge that gender biases hinder true equity, but these insights vary wildly by discipline; stronger in STEM, weaker in humanities where ideology reigns supreme. In the end, it’s all fuelled by hubris: academics think they’re above the fray, crafting a better world, but they’re just propping up a house of cards built on denial of basic human reality. Gender ideology isn’t enlightenment; it’s a collective delusion that crumbles under scrutiny, yet persists because admitting otherwise would humble the proud.

The Gender Ideology Movement: Origins, Science, and Criticisms

Gender ideology, at its core, rests on the claim that gender is performative [a social role or identity detached from biology], something people “do” rather than something rooted in immutable physical reality. From my perspective, this view is fundamentally flawed and intellectually dishonest. It treats gender as a malleable script anyone can rewrite at will, ignoring the overwhelming biological evidence that sex is binary and foundational to human development. Proponents insist gender is a fluid, socially constructed phenomenon, but in reality, this ideology peddles a denial of basic biology under the guise of liberation. It elevates subjective feelings over objective facts, leading to absurd outcomes where biological males compete in women’s sports or enter women’s spaces, all justified by the notion that personal declaration trumps chromosomes, hormones, and anatomy.

The term “gender ideology” itself emerged in the 1990s, primarily from Vatican critiques during UN conferences on population, development, and women’s rights (such as Cairo in 1994 and Beijing in 1995). Catholic leaders and allies viewed the push to replace “sex” with “gender” in international documents as a radical attempt to undermine traditional family structures, natural sexual differences, and procreation-focused sexuality. They saw it as an ideological assault promoting a society without fixed male-female distinctions. While framed by supporters as resistance to progress, this origin highlights how the concept was quickly weaponised in cultural debates; yet the underlying ideas predate that label.

Money held the view that affectional paedophilia is caused by a surplus of parental love that became erotic, and is not a behavioural disorder.

The intellectual foundations draw heavily from flawed mid-20th-century figures like John Money and Alfred Kinsey, both tied to paedophilia advocacy. Money pioneered the idea that gender is psychological and malleable, separate from biology, famously through his disastrous “John/Joan” case involving David Reimer. After a botched circumcision destroyed Reimer’s penis as an infant, Money convinced the parents to raise him as a girl, using hormones, surgery, and socialisation to prove nurture could override nature. Money publicly declared it a success, but the truth was catastrophic: Reimer rejected the female identity, suffered immense psychological trauma, transitioned back to male as a teenager, and later died by suicide. His twin brother also committed suicide. This wasn’t proof of gender fluidity, it was a grotesque failure exposing the hubris of treating children as experimental subjects to prop up pseudoscientific theories. Yet gender ideology clings to Money’s discredited framework, ignoring how it led to real harm.

Kinsey’s work contributed by promoting sexuality as a continuum rather than discrete categories, blurring lines in ways that normalised fringe behaviours. His infamous reports included highly controversial data on child sexuality, most notoriously in Table 34 from Sexual Behaviour in the Human Male (1948), which purported to document “orgasms” in pre-adolescent boys, some as young as infants. This table listed timed responses; such as an 11-month-old allegedly experiencing 10 “orgasms” in one hour, or young children reaching dozens in a day, based on observations from adult men who had sexually abused children. Kinsey’s methodology involved relying on these abusers’ accounts, where they timed the children’s reactions (often involving screaming, weeping, convulsions, or fighting) with stopwatches, framing the abuse as consensual or scientifically neutral “sexual responses.”

Sexual Behavior In The Human Male by Alfred C Kinsey (online Book)

Critics, including investigative accounts and former Kinsey associates’ later admissions, point out that much of this data came from a single prolific paedophile (often identified as “Mr. X” or Rex King in revelations from the 1990s), whose detailed diary of assaults on hundreds of children was presented as aggregated from multiple sources. Kinsey did not report these ongoing crimes to authorities, prioritising confidentiality for “honest” data over child protection. While the Kinsey Institute has denied direct payments or experiments by researchers themselves, the reliance on such sources, without ethical safeguards (which would be impossible), has been widely condemned as enabling and sanitising child sexual abuse under the banner of science. From my view, this stains the entire foundation: Kinsey’s continuum thinking fed into gender ideology by suggesting human sexual and gender boundaries are infinitely blurry and negotiable from birth, downplaying moral absolutes and biological realities in favour of radical relativism.

While not directly about gender, this continuum thinking fed into the broader ideology that human differences in sex and attraction are infinitely variable and socially negotiable, rather than grounded in biology. From my view, these origins taint the movement: built on ethical lapses, fabricated successes, and a willingness to overlook, and to incorporate the harming of infants and children, in pursuit of radical redefinitions of human nature.

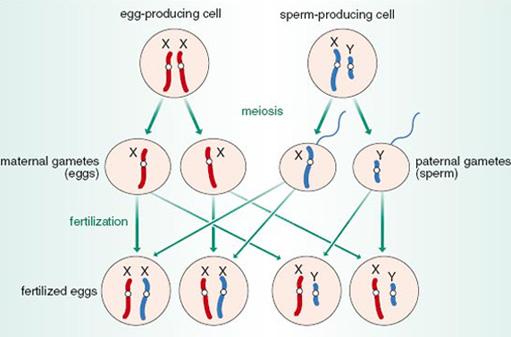

Critics rightly argue that gender ideology lacks solid scientific footing. Biological sex is binary, defined by gametes (sperm or ova production), chromosomes (XX or XY in typical cases), and reproductive anatomy, with rare medical disorders, not evidence of a spectrum. No credible evidence supports an innate “gender identity” independent of sex; claims of brain differences in transgender individuals are small, inconsistent, and confounded by hormone use and socialisation. Studies purporting minimal immutable sex differences exaggerate overlaps while ignoring meaningful averages in behaviour, psychology, and physiology shaped by evolution.

Proponents counter that gender is socially constructed, explaining fluidity through cultural norms rather than biology, and accuse critics of essentialism that reinforces inequality. They cite research showing more similarities than differences between sexes and argue rigid binaries harm those who don’t fit neatly.

In balanced terms, interpretations of sex differences are shaped by ideology: some emphasise construction to promote equity, others see essentialism as justifying hierarchies. But from reality’s standpoint, the evidence overwhelmingly supports sex as binary and foundational. Gender ideology’s push for fluidity minimises these differences to advance a narrative where biology is optional, leading to policies that erode sex-based rights and protections. It thrives not on robust science but on social pressure and academic conformity, much like the groupthink discussed earlier, where dissent is punished and hubris allows flawed ideas to masquerade as progress. In the end, it’s not empowerment; it’s a denial of material reality that harms women, children, and the integrity of truth itself.

Conclusion

Academics fall for such ideologies because their intellectual strengths, analytic prowess, love of complexity, and group cohesion, become liabilities when fused with hubris, echo chambers, and career incentives. The result is a collective delusion where flawed premises masquerade as profound insight, harming truth, vulnerable individuals (e.g., through rushed medical interventions), and society at large by eroding sex-based safeguards and rational discourse.

To counter this, academia must reclaim genuine diversity of thought: fostering viewpoint pluralism, enforcing falsifiability even in interpretive fields, and rewarding dissent over conformity. Only then can the academy fulfil its mission as a bastion of reason rather than a breeding ground for ideological capture. As Shermer warns, intelligence without humility and self-correction leads not to enlightenment, but to ever-more-convincing rationalisations of error. The path forward demands epistemic humility, recognising that the smartest among us are not immune to the frailties that make “weird things” believable, but uniquely equipped to defend them. Breaking free requires courage to confront uncomfortable realities, lest the pursuit of truth devolve into the comfort of consensus.

Glossary of Terms

- Binary (in biology/sex): Referring to the classification of biological sex as consisting of two distinct categories; male and female, defined primarily by the production of small gametes (sperm) or large gametes (ova/eggs), with rare medical exceptions (e.g., disorders of sex development) still fitting within this framework rather than creating additional categories.

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to seek out, interpret, or favour information that confirms one’s pre-existing beliefs while ignoring or downplaying contradictory evidence.

- Continuum (in gender studies): The idea that gender (or sometimes aspects of sex) exists as a spectrum or range of variations rather than strict, discrete categories, allowing for degrees of traits, identities, or expressions between or beyond traditional male/female poles.

- Deconstructing (in postmodernism/gender theory): The process of critically analysing and dismantling established concepts, binaries (e.g., male/female), or assumptions to reveal their constructed, contingent, or power-based nature, often associated with thinkers like Judith Butler in challenging essentialist views of gender.

- Dogmatic: Characterised by the unquestioning acceptance of principles or beliefs as absolute truth, often resistant to evidence or alternative views.

- Empirical: Based on observation, experience, or experiment rather than theory or pure logic; relying on verifiable evidence.

- Endocrinology: The branch of medicine and biology that studies the endocrine system, including glands (e.g., thyroid, adrenals) and hormones (e.g., oestrogen, testosterone), and their role in regulating bodily functions, development, and sex differences.

- Epistemological: Relating to epistemology, the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature, sources, and limits of knowledge.

- Essentialism: The philosophical view that certain categories (e.g., male/female) have inherent, fixed properties or essences that define them, often contrasted with social constructionism.

- Falsifiability: A criterion proposed by philosopher Karl Popper, stating that a scientific theory must be capable of being tested and potentially proven false through evidence.

- Fluidity (gender fluidity): A non-fixed gender identity that shifts over time, situations, or contexts; individuals may experience changes in how they identify or express gender, rather than maintaining a static category.

- Gametes: Reproductive cells, such as sperm (produced by males) or ova/eggs (produced by females), which define biological sex in organisms.

- Gender Performativity: A theory by Judith Butler positing that gender is not an innate trait but a series of repeated acts, behaviours, and performances shaped by cultural norms.

- Groupthink: A psychological phenomenon, described by Irving Janis, where a group’s desire for harmony and conformity leads to irrational or dysfunctional decision-making, suppressing dissent.

- Heuristics: Mental shortcuts or rules of thumb that simplify decision-making, often leading to biases or errors in judgment. A rule or piece of information used in or enabling problem-solving or decision-making.

- Hubris: Excessive pride or self-confidence, often leading to overestimation of one’s abilities or knowledge.

- Incommensurable: Referring to Thomas Kuhn’s idea that competing scientific paradigms or worldviews cannot be directly compared because they operate under fundamentally different assumptions and frameworks. Not able to be judged by the same standards; having no common standard of measurement.

- Locus of Control: A psychological concept describing the degree to which individuals believe they control events in their lives (internal locus: personal actions; external locus: outside forces like fate or society).

- Magical Thinking: The belief that unrelated events are causally connected or that thoughts, symbols, or rituals can influence outcomes without empirical evidence.

- Motivated Reasoning: The process of using reasoning skills to justify or defend beliefs that align with one’s emotions, identities, or preconceptions rather than objectively evaluating evidence.

- Objectivity: In science and philosophy, the quality of claims, methods, or knowledge being independent of personal biases, perspectives, or value judgments; often seen as faithfulness to facts or evidence, though debated in terms of full attainability due to theory-laden observations.

- Paradigms: In Thomas Kuhn’s theory, dominant frameworks or models in science that define the rules, assumptions, and methods of inquiry within a field, resistant to change until a crisis occurs. A typical example or pattern of something; a pattern or model.

- Pluralism (viewpoint pluralism): The recognition and acceptance of multiple valid perspectives, theories, or truths coexisting (e.g., in academia, encouraging diversity of thought rather than a single dominant ideology), often contrasted with monism or dogmatic uniformity.

- Postmodernism: A philosophical movement, associated with thinkers like Michel Foucault, that questions objective truth, emphasising that knowledge is shaped by power structures, culture, and subjectivity.

- Proponents: Advocates or supporters of a particular idea, theory, or ideology (in the article, often referring to those who defend gender ideology as a valid social constructionist framework).

- Pseudoscience: Claims or beliefs presented as scientific but lacking empirical support, rigorous testing, or falsifiability, often relying on anecdotal evidence or flawed methodology.

- Rationalism: A philosophical approach emphasising reason and logic as the primary sources of knowledge, often contrasted with empiricism.

- Rigorous: Involving strict precision, thoroughness, and adherence to high standards, especially in inquiry or analysis.

- Social Constructionism: The theory that aspects of reality, such as gender or knowledge, are created and maintained through social processes, interactions, and cultural norms rather than being inherent or natural.

Additional References

- Allarakha, S. (2021). What Are the 72 Other Genders?. MedicineNet. Available at: https://www.medicinenet.com/what_are_the_72_other_genders/article.htm [Accessed 17 January 2026].

- Austin, M. P. (1999). Paradigms in ecology. Ecology, 83(6).

- Balanko, S. L. (2002). Teaching about sexuality: Balancing contradictory social messages children receive about sex. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 93(4), 310-313.

- Bancroft, J. (1998). Alfred Kinsey’s work 50 years later. In J. Bancroft (Ed.), Sexual development in childhood (pp. 3-16). Indiana University Press.

- Bernstein, M. (2003). Nothing Ventured, Nothing Gained? Conceptualizing Social Movement “Success” in the Lesbian and Gay Movement. Sociological Perspectives, 46(3), 353-379.

- Boynton, R. (1995). The abduction. Esquire.Cohen, M. (2015). Paradigm shift revisited. Asterisk Magazine.

- Crockford, S. (2023). Cults in context. Equinox Publishing.

- DeCecco, J. P. (1991). Paidika interview. Paidika: The Journal of Paedophilia.

- Deslippe, P. (2023). Cults in popular culture. Equinox Publishing.

- Eagly, A. H. (2018). The shaping of science by ideology: How feminism inspired, led, and constrained scientific understanding of sex and gender. Journal of Social Issues, 74(4), 871-888.

- Fine, C., Joel, D., Jordan-Young, R., Kaiser, A., & Rippon, G. (2013). Plasticity, plasticity, plasticity… and the rigid problem of sex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(11), 550-551.

- Finneran, T. (2023). You’re Not Too Smart to Join a Cult. Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/@tudorfinneran/youre-not-too-smart-to-join-a-cult-why-intelligent-people-fall-for-sophisticated-manipulation-17da33dcde73 [Accessed 17 January 2026].

- Fiske, S. T. (1949). Social unity in cults. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology.

- Ger, M. (2018). Religiosity and intelligence. Journal of Religion and Health.

- Goodrich, H. F., & Wolkin, P. A. (1961). The Story of the American Law Institute.

- Harbinger, J. (2021). Michael Shermer: Why We Believe Weird Things. The Jordan Harbinger Show. Available at: https://www.jordanharbinger.com/michael-shermer-why-we-believe-weird-things [Accessed 17 January 2026].

- Haskins, R., & Bevan, C. S. (1997). Abstinence education under welfare reform. Children and Youth Services Review, 19(5-6), 465-484.

- Hazard, G. C. (1994). The American Law Institute.

- Hengeveld, R., & Walter, G. H. (1999). The two coexisting ecological paradigms. Acta Biotheoretica, 47(2), 141-170.

- Hogg, M. A., & Turner, J. C. (1987). Intergroup behaviour, self-stereotyping and the salience of social categories. British Journal of Social Psychology, 26(4), 325-340.

- Irvine, J. M. (2002). Talk about sex: The battles over sex education in the United States. University of California Press.

- Jones, J. H. (1997). Alfred C. Kinsey: A public/private life. W.W. Norton.

- Kane, M. D. (2007). Timing Matters: Shifts in the Causal Determinants of Sodomy Law Decriminalization, 1961–1998. Social Problems, 54(2), 211-239.

- Kiefer, A. K., & Sekaquaptewa, D. (2007). Implicit stereotypes and women’s math performance. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(1), 65-75.

- Kimmel, M. (2017). The Gendered Society. Oxford University Press.

- Kinsey, A. C. (1948). Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. W.B. Saunders.

- Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

- Lalich, J. (2017). Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Cults. University of California Press.

- Lane, K. A., Goh, J. X., & Driver-Linn, E. (2012). Implicit science stereotypes mediate the relationship between gender and academic participation. Sex Roles, 66(3-4), 220-234.

- Littman, L. (2018). Parent reports of adolescents and young adults perceived to show signs of a rapid onset of gender dysphoria. PLOS ONE, 13(3), e0202330.

- Luders, A., Jonasdottir, S., & Unnsteinsdottir, K. (2016). Personality traits and cult recruitment. Personality and Individual Differences.

- Lynch, G. E. (1998). Towards a Model Penal Code, Second (Federal?): The Challenge of the Special Part. Buffalo Criminal Law Review, 2(1), 297-320.

- Mayer, L. S., & McHugh, P. R. (2016). Sexuality and Gender: Findings from the Biological, Psychological, and Social Sciences. The New Atlantis, 50.

- Money, J. (1973). Gender Role, Gender Identity, Core Gender Identity: Usage and Definition of Terms. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 1(4), 397-402.

- Nosek, B. A., & Smyth, F. L. (2011). Implicit social cognitions predict sex differences in math engagement and achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 48(5), 1125-1156.

- Nosek, B. A., Smyth, F. L., Sriram, N., Lindner, N. M., Devos, T., Ayala, A., … & Greenwald, A. G. (2009). National differences in gender–science stereotypes predict national sex differences in science and math achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(26), 10593-10597.

- Pear, R. (1986). Reagan signs bill tying aid to states to abstinence education. New York Times.

- Pierre, J. (2025). False: How Mistrust, Disinformation, and Motivated Reasoning Make Us Believe Things that Aren’t True. UC San Francisco Press.

- Reisman, J. (2017). Amicus Brief in Gloucester County School Board v. G.G.. Supreme Court of the United States.

- Rousselet, M., Duretete, O., Hardouin, J. B., & Grall-Bronnec, M. (2017). Cult membership: What factors contribute to joining or leaving?. Psychiatry Research, 257, 27-33.

- Rypel, A. L., Saffarinia, P., Vaughn, C. C., & Nerenberg, L. (2021). Goodbye to “rough fish”: Paradigm shift in the conservation of native fishes. Fisheries, 46(12), 605-616.

- Shapere, D. (1964). Review of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Philosophical Review, 73(3), 383-394.

- Sheehan, M. (2019). Paradigms in ecology. Routledge.

- Shermer, M. (2002). Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time. Holt Paperbacks.

- Simberloff, D. (1980). A succession of paradigms in ecology: Essentialism to materialism and probabilism. Synthese, 43(1), 3-39.

- Singer, M. T. (1996). Cults in Our Midst. Jossey-Bass.

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Basil Blackwell.

- Wada, M., Backman, C. L., & Forwell, S. J. (2010). Theoretical perspectives of balance and the influence of gender ideologies. Journal of Occupational Science, 17(2), 92-103.

- Walter, G. H., & Hengeveld, R. (2000). The structure of ecological science. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 204(1), 105-113.

- Wu, J., & Loucks, O. L. (1995). From balance of nature to hierarchical patch dynamics: A paradigm shift in ecology. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 70(4), 439-466.

- Zuckerman, M., Silberman, J., & Hall, J. A. (2013). The relation between intelligence and religiosity: A meta-analysis and some proposed explanations. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 17(4), 325-354.