Introduction: Why Responding to the DfE Consultation on Keeping Children Safe in Education Matters for Safeguarding Our Children in Schools

In a statement released on February 12, 2026, Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson emphasised the government’s commitment to child safety, drawing on evidence from Dr. Hilary Cass’s expert review to provide teachers with clear guidance on supporting gender-questioning children. Phillipson highlighted that parents trust schools to protect their children, and this consultation on revisions to the statutory Keeping Children Safe in Education (KCSIE) guidance for September 2026 aims to deliver pragmatic support for educators, reassurance for families, and, above all, the wellbeing of Children.

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-to-publish-new-gender-guidance-for-schools

LEGALLY SCHOOLS & COLLEGES MUST:

- Provide separate toilets for boys and girls aged 8+ (except lockable single-user rooms). Must not allow entry to opposite-sex designated toilets, even for social transition requests.

- Provide suitable changing/shower facilities for pupils aged 11+ at the start of the school year, segregated by biological sex. Must not allow undressing in front of opposite-sex children, with no exceptions for social transition.

- Must not allow sharing with opposite biological sex during overnight/boarding accommodation. No exceptions for social transition.

- Accurately record and share biological sex for safeguarding. All relevant staff must know a child’s biological sex.

- Can separate by biological sex where physical differences (strength, stamina, physique) disadvantage one sex, with no exceptions for safety-critical cases. For fairness reasons, requests must be considered cautiously, balancing best interests and peer impact.

- Must not initiate Social Transition Requests; respond only to child/parent requests. Involve parents/carers as priority (unless significant harm risk). Document decisions, consult DSL/SENCO/clinicians if needed. Take cautious approach, especially pre-puberty. Comply with Equality/Human Rights Acts, assess discrimination risks and alternatives.

- Integrate awareness of vulnerabilities (e.g., transphobic bullying, sexual violence) into policies.

The draft integrates long-awaited advice on gender-questioning children, urging a cautious approach to any requests for social transition, with parental involvement required in the vast majority of cases and no unilateral changes by staff. However, myself and organisations like Transgender Trend, Sex Matters, Safe Schools Alliance and others argue that this consultation represents a critical opportunity to go further in protecting children from potential harm.

Transgender Trend, in their response to similar past consultations, stresses the need for an evidence-based “watchful waiting” approach over “gender affirmative” models, warning that social transition can entrench dysphoria, ignore underlying issues like autism or trauma, and pave the way for unproven medical interventions with lifelong risks, such as bone density loss from puberty blockers or elevated suicide risks post-treatment, as evidenced by studies like Sweden’s 2022 Karolinska Institute review. They urge responders to push for guidance that fully aligns with the Cass Review’s findings, which highlight a lack of robust evidence for social transition’s benefits and note desistance rates of 80-95% in pre-pubertal children if not affirmed.

Sex Matters welcomes the statutory integration but calls for unambiguous sex-based policies, insisting schools must record biological sex accurately and bar access to opposite-sex facilities without exception. Their analysis emphasises that ambiguities in the draft could undermine single-sex spaces, risking privacy, safety, and fairness, particularly in sports or changing rooms, while excluding parents in rare cases invites unnecessary harm. They advocate responding to eliminate any allowances for social transition, arguing it normalises a framework lacking empirical support and could lead to medicalisation in up to 96% of affirmed cases, per 2011 research.

Safe Schools Alliance views the draft as insufficient; a “sticking plaster on a severed limb”, and has long criticised delays in clear guidance, which they say have allowed ideological influences to erode safeguarding. They contend that any form of transition in schools, even limited, violates child protection by facilitating changes without medical oversight, potentially amplifying distress rather than resolving it, and disregarding comorbidities in 20-30% of referrals (per Tavistock data). Responding en masse, they argue, is essential to demand a outright ban on social transitions, ensuring schools prioritise biology, parental rights, and evidence over activism.

Completing the Consultation Feedback Form

This consultation closes in 10 weeks, and your input could shape policies that prevent schools from enabling any transition elements, safeguarding children from irreversible decisions amid a 400% surge in youth referrals. In the following sections, I’ll guide you question by question through the form, providing insights to help craft responses that prioritise child welfare. Many of the questions have a character limit for responses – so I have had to curtail my responses to fit!

Privacy notice

Please note: Information provided in response to consultations, including personal information, may be subject to publication or disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act 2000, the Data Protection Act 2018 or the Environmental Information Regulations 2004.

- If you want all, or any part, of a response to be treated as confidential, please explain why you consider it to be confidential.

- If a request for disclosure of the information you have provided is received, your explanation about why you consider it confidential will be taken into account, but no assurance can be given that confidentiality can be maintained. An automatic confidentiality disclaimer generated by your IT system will not, of itself, be regarded as binding on the Department.

- The personal data (name and address and any other identifying material) that you provide in response to this consultation is processed by the Department for Education as a data controller in accordance with the UK GDPR and Data Protection Act 2018, and your personal information will only be used for the purposes of this consultation.

- The Department for Education relies upon the lawful basis of article 6 (1) (e) of the UK GDPR which process this personal data as part of its public task, which allows us to process personal data when this is necessary for conducting consultations as part of our function. Your information will not be shared with third parties unless the law allows or requires it.

- You can read more about what the Department for Education does when we ask for and hold your personal information in our personal information charter, which can be found here: Personal information charter – Department for Education – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk).

- We may also use Artificial Intelligence (AI) to conduct qualitative analysis on some of the responses submitted to this consultation.

Click here to Start: https://consult.education.gov.uk/independent-education-and-school-safeguarding-division/keeping-children-safe-in-education-2026-revisions/consultation/intro

About You:

In the About you section (which comes first and includes required fields like capacity as “Parent or Carer”, “Member of the public”, or “Other”), select the options that best fit you:

Full List of Questions in “About You”

1. What is your name? Name (Required)

2. What is your email address? Email address (Required)

3. What is the name of your organisation? (Required)

- Individual

- Organisation – Please provide the name of your organisation

4. What type of organisation is it? (Required)

- Nursery – Primary School – Secondary School – Multi Academy Trust – Sixth Form – FE – HE – Union – Charity – Training provider – ITT Training provider – Consultancy – Other – If other, please state: – Not applicable

5. In what capacity are you responding? (Please select most applicable)(Required)

- Teacher – Head Teacher or Principal – Other Senior Management – Designated Safeguarding Lead (or deputy DSL) – Trainee Teacher/Teaching Assistant – Parent or Carer – Trainer – Consultant – Official – Other – If other, please state:

6. In which local authority is your organisation based? (If not applicable got to Q7.)

Answer (free text):

7. How many staff are employed at your organisation? (Required)

- 1-10 11-50 51-200 201-500 500+

- Not sure / Prefer not to say

8. How many learners does your organisation support? (Required)

- Fewer than 50 50-200 201-500 501-1000 1000+

- Not applicable / Don’t know

9. How long have you worked in education or your current sector?(Required)

- Less than 1 year 1-5 years 6-10 years 11-20 years Over 20 years

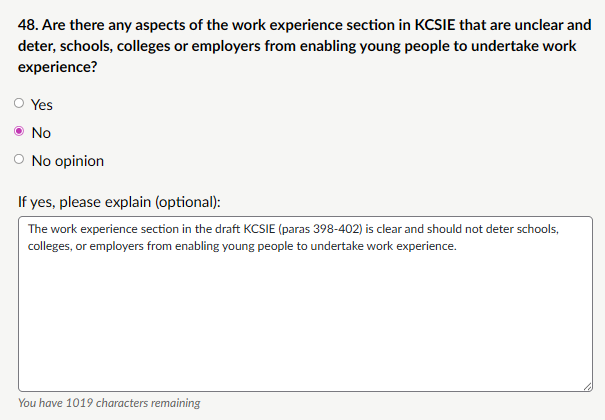

- I’ve never worked in education or safeguarding

10. Would you like us to keep your responses confidential? (Required)

If yes, please provide a reason for confidentiality. Please see the privacy notice. Yes / No – If yes, please provide a reason for confidentiality

Section 1 – Summary of the guidance

11. How do you typically access and refer to the KCSIE guidance?

- I print a copy to read and refer to

- I read and refer to it electronically (e.g. PDF, online link)

- I use both printed and electronic formats

- Other (please specify)

- No opinion

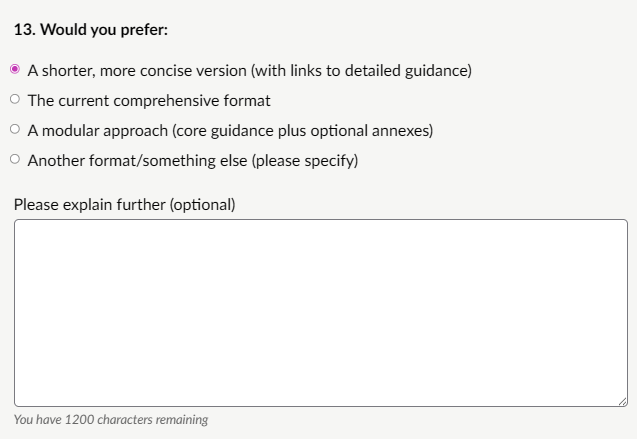

14. What benefits or challenges do you foresee in moving from a PDF to HTML format? Answer (free text) –

My response: “HTML supports screen readers, adjustable text size, and better navigation for disabled users, aligning with WCAG standards and reducing barriers for staff with visual/motor impairments. HTML allows quick revisions without republishing full PDFs, essential for annual KCSIE changes and reducing version confusion. Staff can search, hyperlink to sections, or use mobile devices more effectively; PDFs are harder to navigate on phones or when printing is limited. Smaller file sizes reduce data/emissions, and no need for PDF software. Complex tables, annexes, or printable formats (e.g., for training handouts) may need redesign, risking readability if not done well. Schools with poor internet may struggle; PDFs enable easy offline/download. Many staff/print trainers are accustomed to PDFs; shift may require training or dual formats temporarily. Overall, HTML would make KCSIE more modern, inclusive, and practical for busy educators, provided offline options (e.g., printable HTML versions) and robust testing are included.”

My response: “Yes – a concise one-page summary of Part one (Safeguarding information for all staff) would be extremely helpful. Part one is the most critical section that every staff member must read annually, but the full KCSIE is lengthy (187 pages in 2025 version), leading to overload and inconsistent engagement. A one-page summary would: Reinforce key must-knows (e.g., signs of abuse, what to do if concerns arise, child-centred approach) without overwhelming busy teachers/support staff. Aid induction, refresher training, and quick reference during busy terms. Improve compliance and safeguarding outcomes by making essential info more accessible and memorable. Complement existing resources like the separate Part one PDF, acting as a handy poster/checklist for staffrooms or INSET days.”

EYFS Framework

Proposal and rationale: Stakeholder feedback has highlighted that schools are sometimes unaware of the additional safeguarding requirements set out in the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) framework, particularly for children in reception year. To address this, we have clarified that this statutory guidance applies to school-based nurseries and reception classes for children aged 0–5, by explicitly referencing the EYFS.

My response: “Yes, I was aware that the Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS) framework sets out additional safeguarding requirements for children in school-based nurseries and reception classes (ages 0–5). The EYFS Statutory Framework (current version 2024/2025) includes a dedicated safeguarding and welfare section (Section 3), which imposes specific duties beyond general KCSIE. To avoid overload, the DfE could consider a dedicated one-page cross-reference summary of key EYFS-KCSIE alignments for reception staff, similar to the proposed Part one summary. This would aid compliance without adding length to the main document.”

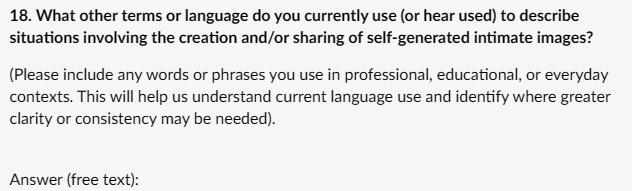

Consensual and non-consensual sharing of nude and semi-nude images and/or videos (also known as sexting or youth produced sexual imagery)

Proposal and rationale: KCSIE currently uses the terminology “Consensual and non-consensual sharing of nude and semi-nude images and/or videos (also known as sexting or youth produced sexual imagery)”. Following stakeholder feedback, we propose to change this language to “consensual and non-consensual self-generated intimate images and/or videos including those generated using AI e.g. deepfakes”. This change in language aims to improve clarity, consistency with current safeguarding terminology, and better reflect the seriousness of both consensual and non-consensual image sharing.

My response: “While the intention is valid and important, the new phrasing introduces problems that could undermine clarity, consistency, and effective safeguarding: Major stakeholders (NSPCC, UK Safer Internet Centre, Internet Watch Foundation, police forces) continue to use “sexting” and “youth produced sexual imagery” in training and resources. Changing makes it harder for schools to align with multi-agency partners, and national toolkits. Keep the current terminology (“Consensual and non-consensual sharing of nude and semi-nude images and/or videos (also known as sexting or youth produced sexual imagery)”) and add a new bullet or sentence in the section: “Schools and colleges should also be aware of the creation and sharing of AI-generated intimate images and videos (including deepfakes) of children, which constitute a form of child sexual abuse material and require immediate referral to police and UK Internet Watch Foundation.” This maintains clarity, legal accuracy, consistency with established safeguarding language, and appropriately highlights the new threat of AI without diluting the focus on youth-produced imagery. (I had more to say but the character limit is very limiting)!”

My response: “Youth produced sexual imagery (YPSI), Sexting, Nude/semi-nude image sharing or sharing of nude and semi-nude images, Self-generated intimate images or self-produced intimate images, Image-based sexual abuse (IBSA), Nudes, nudes/sexts, sending nudes – very common in everyday/peer language, Deepfakes or AI-generated intimate images, Child-generated CSAM. When teaching RSHE it is important to also be aware of language used by pupils such as: Trading nudes, pic for pic, or NP4NP (Nude Pic For Nude Pic) – Pics, dick pics, nude selfies, or tit pics – Dirties – GNOC (Get Naked On Cam) etc. Strong recommendation for consistency: Retain youth produced sexual imagery (YPSI) as the primary formal term in KCSIE because it is precise, legally aligned (images of under-18s are indecent regardless of consent), widely understood across agencies, and avoids normalising language like “consensual” or “self-generated” which can confuse staff about criminal thresholds. Add explicit mention of AI-generated/deepfake intimate images as a separate but related emerging risk, rather than merging it into the YPSI heading. This maintains clarity and prevents dilution of focus on the core youth-produced issue.”

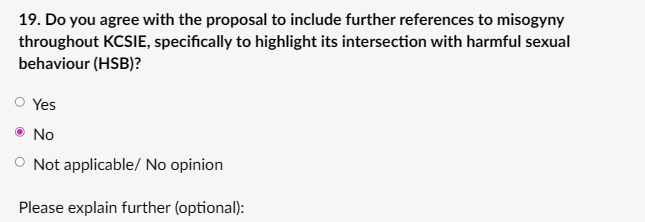

Misogyny

Proposal and rationale: The current KCSIE guidance already includes references to misogyny, however we propose to include further references throughout the guidance to explicitly address where misogyny intersects with harmful sexual behaviour (HSB). Extreme misogyny is increasingly prevalent online and is often linked to harmful sexual behaviour amongst young people. Misogynistic ideologies can contribute to:

- The normalisation of sexual harassment and sexual violence

- Child-on-child exploitation and coercion

- The spread of harmful narratives

My response: “I do not agree with adding further references to misogyny throughout KCSIE without balancing it with discussions of misandry adopting a more neutral approach to harmful sexual behaviour (HSB). While evidence shows misogyny is prevalent online and linked to HSB, 90% of girls vs 50% of boys experience unwanted explicit images, focusing solely on misogyny risks a one-sided narrative that alienates boys and frames them as inherent perpetrators. This could exacerbate male disenfranchisement, as critics argue anti-misogyny lessons are “silly gimmicks” that stigmatise boys without addressing root causes like societal rewards for feminine traits over masculine ones. Teaching teenagers, I have to agree with the critics, there are far better ways to deal with this issue: Emphasise mutual respect, kindness in relationships, and challenging all prejudice (including misandry) via RSHE’s focus on positive role models for both sexes. Teach about harmful narratives without blame to avoid division and promote true safeguarding for everyone. If misogyny is highlighted, misandry must be too for equity under the Equality Act.”

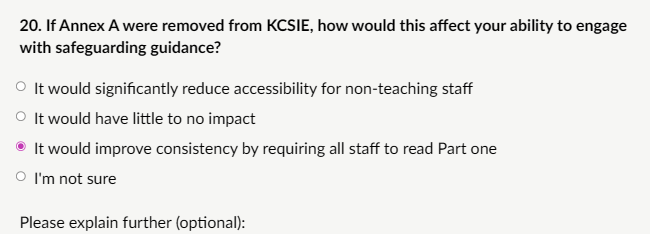

My response: “Removing Annex A would improve consistency and strengthen overall safeguarding awareness across the entire school or college workforce. Part one is already the core, concise summary of essential safeguarding knowledge that every member of staff—teaching and non-teaching—must read and understand annually. It is deliberately written to be accessible (currently around 10–12 pages in the 2025 version), covering key signs of abuse, what to do if a concern arises, the child-centred approach, and basic responsibilities without overwhelming detail. Requiring everyone to read the same Part one document would: Promote a unified safeguarding ethos where all adults in the setting understand their shared responsibility. Reduce confusion over which version to use and simplify annual training/induction processes. Align with the principle that safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility, not just those in direct child-facing roles. Overall, removing Annex A would be a positive step toward higher standards, greater consistency, and better protection for children by ensuring no staff member has a diluted version of the essential guidance.”

What school and college staff need to know

Proposal and rationale: To align with Working Together to Safeguard Children (WT), we have made changes to paragraphs 13-14 and paragraph 65. Aligning KCSIE with WT promotes consistency across the safeguarding system and clarifies schools’ roles within multi-agency arrangements.

My response: “I agree with the proposed changes to paragraphs 13–14 and paragraph 65 to better align KCSIE with Working Together to Safeguard Children (WTSC 2023). This promotes much-needed consistency across the multi-agency safeguarding system and clarifies the specific role of schools and colleges within those arrangements to :Reinforce that safeguarding is a shared, multi-agency responsibility (as per WTSC Chapter 2), where schools contribute actively to local safeguarding partnerships (LSPs), early help, child protection enquiries, and information sharing. Update paragraph 65 to explicitly require governing bodies/proprietors to ensure the school/college contributes to multi-agency working in line with WTSC, including engaging with LSPs, relevant agencies, and processes like strategy discussions or child protection conferences. Clarify paragraphs 13–14 (likely in the “Safeguarding information for all staff” or early help sections) to reflect WTSC’s emphasis on schools’ pivotal role as often the first point of contact for concerns, their duty to provide early help where appropriate, and integration into the broader system of help, support, and protection.”

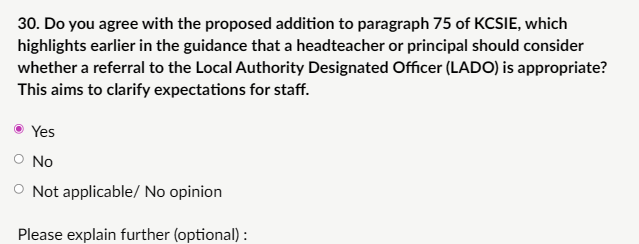

Early help

Proposal and rationale: Following stakeholder feedback, we have suggested amendments to paragraph 17 in the draft of KCSIE 2026 to include “…has been repeatedly removed from the classroom…” to reflect the Behaviour in Schools guidance around causes and responses to misbehaviour. And also “…is on a part-time timetable…”, which can be a contributing factor towards child criminal exploitation.

My response: “I agree with the proposed amendments to paragraph 17 of KCSIE 2026, which add references to pupils who have been “repeatedly removed from the classroom” and those “on a part-time timetable” as factors that may indicate a need for early help. These changes better reflect the DfE’s Behaviour in Schools guidance (February 2024 version) and highlight genuine safeguarding risks, particularly child criminal exploitation (CCE), including county lines involvement. Repeated removals can signal underlying issues like disengagement, unmet needs (e.g., SEND), or escalating vulnerability. Linking this to early help in KCSIE is appropriate, as persistent removal may indicate risks such as poor attendance patterns, mental health concerns, or exposure to exploitation outside school. It aligns with the guidance’s emphasis on proportionate, transparent use of removal and reintegration processes to avoid alienation. Official DfE-aligned local authority guidance states pupils of compulsory school age are entitled to full-time education, and part-time timetables should be exceptional, time-limited (often max 6 weeks), consensual, and not used for behaviour management.”

Child Sexual Exploitation

Proposal and rationale: The current wording of paragraphs 26 and 39 of KCSIE risks creating confusion about the legal definition of rape. Under UK law, rape occurs when a person uses their penis without consent to penetrate the vagina, anus, or mouth of another person. Phrases such as “rape or oral sex” may imply that non-consensual oral penetration by a penis is not rape, which is incorrect. To improve clarity, we propose removing this phrasing and adding an example of penetration with an object, which is legally recognised as a distinct form of sexual assault.

My response: “I agree that the proposed changes to paragraphs 26 and 39 improve clarity around the legal definition of rape and sexual assault under the Sexual Offences Act 2003 (section 1), which defines rape precisely as intentional penetration of the vagina, anus, or mouth with a penis, without consent and without reasonable belief in consent. The current wording in KCSIE (e.g., 2025 version, paragraph 27 on sexual abuse and paragraph 33 on child-on-child abuse) includes phrases like “assault by penetration (for example rape or oral sex)” or “sexual violence such as rape, assault by penetration and sexual assault.” This can create confusion because: Non-consensual oral penetration by a penis is rape under section 1—so listing “rape or oral sex” separately risks implying that oral rape is not “real” rape or is a lesser/different offence. Accurate terminology supports better safeguarding, especially in child sexual exploitation (CSE) or child-on-child cases where precise recognition of offences is vital for risk assessment and response.”

My response: “I agree that the revised wording in paragraph 41 helps education professionals better understand the risk of victims of child sexual exploitation (CSE) being criminalised for actions taken under coercion. The update reflects evidence from the Baroness Casey National Audit on Group-based Child Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (June 2025), which highlighted how victims—often groomed and coerced—have been treated as perpetrators rather than protected, including through criminal convictions for offences committed under duress (e.g., drug-related activities, theft, or prostitution offences forced by exploiters). The report notes victims living with the “constant shadow” of injustice, stigma, and unaddressed convictions, exacerbating trauma and distrust in authorities. Suggestions: Add a brief cross-reference to the Casey Audit key findings, Include practical prompts for DSLs: “When a child is involved in offending, consider CSE/CCE indicators and refer to multi-agency partners before assuming criminality.” Emphasise support for victims with historic convictions, linking to government review processes. Ensure wording avoids normalising coercion—frame it clearly as abuse, not “choice.” “

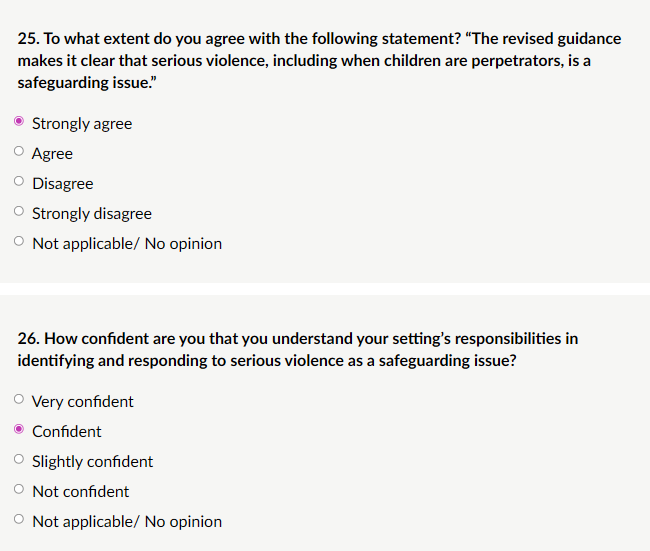

Serious violence

Proposal and rationale: We have clarified that violence between children may, in some instances, constitute a safeguarding issue, particularly where there is a risk of harm, exploitation, or vulnerability. The guidance now includes:

- explicit references to physical assault and threats with weapons.

- recognition that children who display violent behaviour may themselves be at risk or in need of support.

- a strengthened message that safeguarding responses should consider both the child who has been harmed and the child who has caused harm.

This change reflects stakeholder feedback and aligns with a more trauma-informed approach to safeguarding.

My response: “Checklists, Clearer definitions, Partner roles: checklists would be most helpful for quick reference in identifying risk indicators (e.g., escalation from verbal threats to weapon-carrying, peer group dynamics, unexplained injuries, changes in behaviour). Clearer definitions are also needed to distinguish serious violence (requiring immediate safeguarding/police response) from lower-level conflict, avoiding over- or under-reaction. Partner roles (e.g., police under Serious Violence Duty, youth offending services, children’s social care, early help teams) would clarify multi-agency pathways and prevent silos. These additions would keep KCSIE practical and focused without excessive length, supporting consistent, trauma-informed responses across schools and colleges.”

What school and college staff should do if they have a safeguarding concern or an allegation about another member of staff

Proposal and rationale: Following stakeholder feedback, we have added wording to paragraph 75 to highlight earlier in the guidance that the headteacher or principal will consider whether a LADO referral is appropriate. This should help staff to understand that this is an expectation.

My response: “This is a helpful and necessary clarification for the following reasons: Timely and consistent decision-making. Reinforces statutory expectations: Under Working Together to Safeguard Children (2023) and KCSIE itself (paragraphs 391–418 in current versions), headteachers/principals must consider LADO referral, explicitly signposting this duty earlier reduces the risk of concerns being managed informally or internally without LADO consultation, which has been a factor in serious case reviews (e.g., where grooming or abuse was missed due to delayed external oversight).

Supports staff confidence and reduces hesitation: Staff (especially non-DSLs) sometimes worry about “over-reacting” or damaging a colleague’s reputation. By stating earlier that the headteacher/principal should consider LADO referral, it normalises the process, clarifies it is an expectation (not optional), and reassures staff that raising a concern will trigger appropriate professional assessment rather than automatic escalation. Aligns with low-level concerns guidance, improves accessibility, promotes consistency, and strengthens safeguarding culture without adding complexity or length.”

My response: “I disagree that the revised section clearly explains schools’ role in mental health. Teachers are not mental health experts and should not be positioned to identify early signs or provide targeted support beyond basic observation and referral. Research shows over-focus on mental health/wellbeing in schools can be iatrogenic—causing increased anxiety, rumination, or symptom amplification, especially in universal approaches. The redraft risks encouraging non-specialists to “respond confidently” to issues like self-harm or eating disorders without strong enough caveats on professional limits. This could lead to misattribution (e.g., trauma or neurodiversity misread as primary MH problems) or inappropriate interventions. Explicitly state: “School staff are not mental health professionals and must not diagnose, counsel, or treat. Their role is limited to noticing significant changes, offering kind listening, and referring immediately to the DSL and specialist services (e.g., CAMHS).” Prioritise safeguarding intersections only (serious risks like suicide/self-harm as abuse indicators). Strengthen signposting/warn against over-medicalisation or universal MH programmes with known harms.”

My response: “I disagree that the revised section provides a clear and useful high-level summary or appropriately signposts to more detailed guidance. While the intent to clarify intersections between mental health and safeguarding is understandable, the redraft still risks over-extending schools’ role into mental health territory. Teachers and non-specialist staff are not equipped or qualified to identify early signs of issues like eating disorders, self-harm, or suicidal ideation in a diagnostic sense, nor should they be encouraged to provide “targeted support” beyond immediate safety measures and referral.

A truly appropriate high-level summary would: Explicitly limit school staff’s role to: noticing significant, observable changes in behaviour; ensuring immediate safety); and referring without delay.

Strongly caution: School staff are not mental health professionals and must not attempt to assess, diagnose, counsel, or deliver therapeutic interventions. Provide clearer, more prominent signposting to evidence-based external resources and warn against unproven or potentially harmful universal programmes. Without these stronger boundaries and cautions, the section is neither clear nor useful.”

Guidance relating to children who are questioning their gender

Background

We have updated the section on children questioning their gender which focuses on issues that might arise in relation to children who are questioning their gender. We have also proposed separate new sections on single-sex spaces (paragraphs 104-115) and single-sex sports (paragraphs 94-97). These sections are informed by the public consultation on the draft non-statutory Gender Questioning Children: Guidance for Schools and Colleges. We will not be publishing standalone guidance for schools and colleges on gender questioning children, but propose instead to include this content in KCSIE so that children’s wellbeing and safeguarding are considered in the round, and so that schools and colleges can easily access this information in one place.

Proposal and rationale: Overall, the consultation demonstrated that this is a highly contested policy area, with no clear consensus on the appropriate approach, but more respondents expressed negative than positive views about the useability of the draft guidance published for consultation. The Cass Review – an independent review of gender identity services for children and young people – published its final report on 10 April 2024, after this consultation had closed.

By including advice in KCSIE, our intention is to reflect the importance for schools of making careful decisions about what is in the best interests of children, including children who are questioning their gender. Schools and colleges have obligations to safeguard and promote the welfare of all children in their care, and children who are questioning their gender are no exception. Children who are questioning their gender may need sensitive and thoughtful involvement from their school or college. When handled well, with appropriate parental involvement and attention to any clinical input, the school or college’s involvement can help to avoid safeguarding issues arising.

Guidance in this area must be focused on the best interests of children as well as the legal duties of schools and colleges. Our intention is to provide a framework for schools and colleges as they consider these issues. By including this in KCSIE, the advice and framework we are offering will be on a statutory footing.

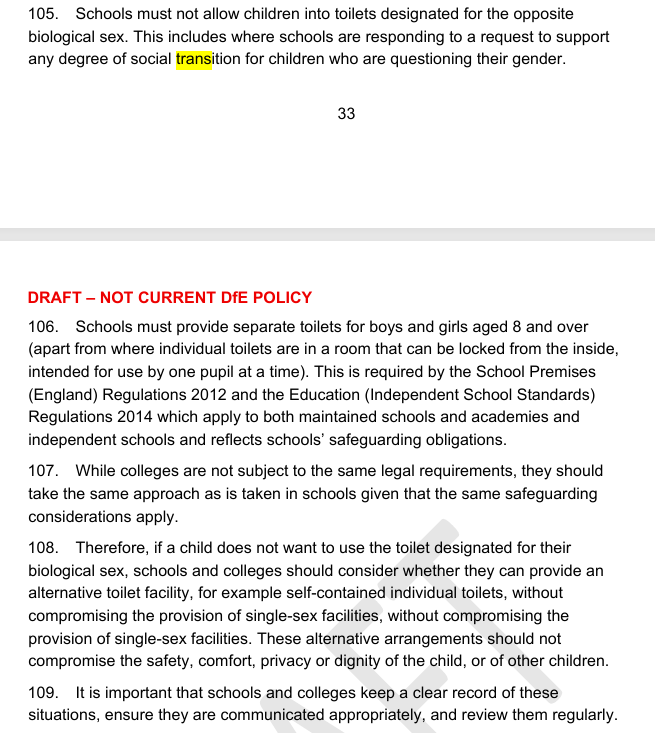

Paragraphs 104-115 and paragraphs 191-196 in KCSIE clarify a school or college’s legal obligations in relation to single-sex spaces, including toilets, changing rooms and boarding / residential accommodation.

The guidance is clear about the law, that schools and colleges should not make exceptions to single-sex policies that are required to comply with statutory requirements and based on safety, but the guidance stresses that where it is both possible and in the interests of the child, schools and colleges should do their best to accommodate the needs of children who are experiencing distress using facilities designated for their biological sex by providing alternative arrangements.

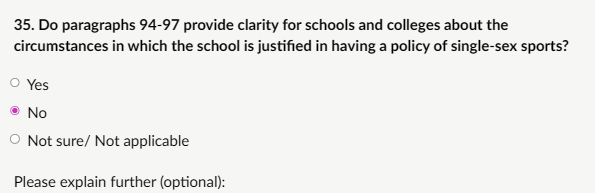

Paragraphs 94-97 clarify the legal issues relating to provision of single-sex sports. Again, where there are safety concerns about mixed-sex provision, we have been clear that sports should be provided in single-sex groups. However, we recognise how important it is that all children can participate in sports and PE, and the draft reflects the importance of considering fairness and safety for all children.

My response: “The updated section lacks clarity and introduces ambiguity by allowing case-by-case social transition (e.g., pronouns/names, even in primary), contradicting the immutability of biological sex as binary and unchangeable. It frames transition as potentially in “best interests” despite Cass Review warnings that it’s an active intervention with unknown long-term effects, increasing medical pathway risks pre-puberty, and vulnerabilities. This enables deception about sex, undermining safeguarding (Children Act 1989) by exposing children to ideological harm, confusion, bullying, or misattributed distress (e.g., neurodiversity/trauma as gender issues). Clarity requires a total ban on social transition; mandate affirmation of biological sex only, immediate parental involvement (unless harm; para 260), clinical referral without school facilitation, and flexible non-stereotyped policies. Equality Act (para 266) protects gender reassignment but prioritises sex-based rights—section allows imbalance by considering exemptions. Document decisions but prohibit any support; support detransition. This protects all children from dangerous ideology.”

My response: “These paragraphs provide strong positive clarity on legal obligations: schools must maintain single-sex toilets (age 8+), changing rooms/showers (age 11+), and boarding accommodation based on biological sex, with no access to opposite-sex facilities even for social transition requests. This is firmly grounded in legislative single-sex exceptions, and safeguarding duties. Colleges should follow the same principles. The core protections uphold biological sex immutability and prevent privacy/dignity invasions, essential for safeguarding all children. However, the caveats weaken this: allowing “alternative arrangements” (e.g., single-user rooms, timed access; “where possible and in the interests of the child” risks indirect stealth living, puberty-related anxiety, or pressure to compromise single-sex provision in practice. Boarding face similar risks. These flexibilities contradict the strict “no exceptions” intent and Cass warnings on vulnerabilities, potentially enabling ideological loopholes that harm collective safety & welfare. Guidance should explicitly prohibit any arrangement that hides or overrides biological sex.”

My response: “These paragraphs offer good clarity on justification for single-sex sports policies under the Equality Act 2010 exception: separation by biological sex is lawful where average physical strength, stamina, or physique disadvantages one sex. Safety-critical cases require no exceptions, and fairness-based policies are permitted. This protects girls and boys from unfair advantage or injury, aligning with biological sex immutability and safeguarding priorities. However, the caveats undermine safeguarding robustness: allows considering requests “in light of” social transition guidance, opens the door to opposite-sex participation where safety is not deemed at immediate risk, despite Cass Review evidence that social transition is non-neutral and lacks long-term outcome data. It risks normalising mutable sex concepts, potential injury, unfairness, or ideological pressure on schools to include gender-questioning children. Full safeguarding requires a blanket prohibition on exceptions in single-sex sports where sex-based rules apply, no case-by-case flexibility that prioritises one child’s distress over collective safety, privacy, or fairness.”

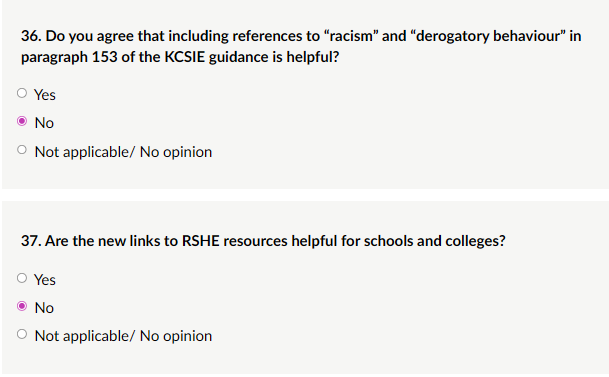

Additional technical updates – other changes to Part two include:

- ‘Opportunities to teach safeguarding,’ included references to ‘racism’ and derogatory behaviour’ and included links to RSHE resources.

- ‘Artificial intelligence,’ proposed the addition of paragraphs focusing on the use of generative artificial intelligence in education.

- ‘Filtering and monitoring’, updates to include an annual review at least every academic year.

- ‘Information security and access management,’ proposed a change of wording with additional information on cyber security.

- ‘Alternative provision,’ additional detail included.

- ‘Medical conditions,’ clarification of safeguarding responsibilities for children with medical conditions, children absent from education, and those in alternative provision.

- ‘Information sharing,’ strengthened guidance on the transfer of child protection files.

Opportunities to teach safeguarding

Proposal and rationale: Paragraph 153 in KCSIE 2026 describes the importance of preventative education and zero tolerance for sexism and other forms of prejudice or harmful behaviour. Including references to “racism” and “derogatory behaviour” in this paragraph aligns the guidance with existing expectations set out in Ofsted’s school inspection framework and the DfE guidance on promoting fundamental British values. This addition reinforces the importance of addressing discriminatory behaviour as part of a whole-school safeguarding approach and supports schools in creating inclusive, respectful environments.

Following stakeholder feedback, we have also updated the wording in paragraph 155 to include new links to RSHE resources: Free, time-saving teacher resources | Oak National Academy

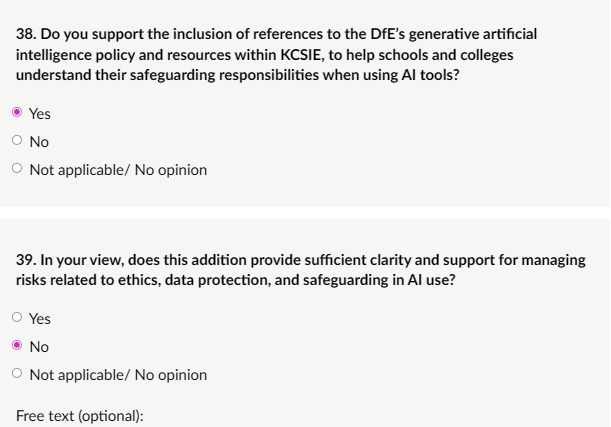

Artificial intelligence (AI)

Proposal and rationale: We are proposing the addition of two new paragraphs after paragraph 159 focusing on AI. The department updated its policy paper on the use of generative artificial intelligence in education. The paper outlines key safety considerations and legal responsibilities for schools and colleges when using generative AI in both teacher-facing and pupil-facing contexts.

To support implementation, the department, working in partnership with the Chiltern Learning Trust and the Chartered College of Teaching, has published online resources for all school and college staff. These resources emphasise safe and effective use of AI, with a strong focus on safeguarding.

My response: “I support including references to the DfE’s generative AI policy paper and the associated online resources (Chiltern Learning Trust / Chartered College of Teaching partnership) in KCSIE. AI is now embedded in education (teacher planning, marking, pupil-facing tools like chatbots or image generators), and schools/colleges need explicit signposting to statutory safeguarding responsibilities when using these tools. Linking to official guidance within KCSIE is helpful for busy DSLs and leaders to understand risks without searching separately. However, the addition does not provide sufficient clarity or robust support for managing the key risks of ethics, data protection, and safeguarding. The current proposal appears limited to high-level references and general “safe and effective use” emphasis, which is inadequate given the serious, child-specific dangers generative AI poses in 2026. Major safeguarding gaps that need stronger coverage: Child sexual abuse material (CSAM) generation, Grooming and radicalisation facilitation, Data protection and privacy breaches, Ethical and bias risks and Low-level concerns and staff misuse.”

Filtering and monitoring

Proposal and rationale: KCSIE currently states that “…governing bodies and proprietors should ensure their school or college has appropriate filtering and monitoring systems in place and regularly review their effectiveness.” paragraph 166.

Following recent ministerial commitments and cross government work to strengthen school and college online safety, we propose adding that governing bodies and proprietors should ‘carry out a review of their effectiveness at least once every academic year’, and that ‘Reviews should include checks that filtering is working appropriately on all internet-connected devices in all relevant locations, and a record should be kept of these checks.’

This wording is already used in the filtering and monitoring standards and reflects expectations that schools and colleges proactively assure the effectiveness of their systems.

Annual, documented reviews are essential to demonstrate that schools and colleges are taking timely and effective action to keep children safe online, particularly given the increasing risks from harmful digital content, AI generated material, and rapid changes in online behaviour.

My response: “I agree with the proposed change to paragraph 166 requiring governing bodies and proprietors to carry out a review of filtering and monitoring systems’ effectiveness at least once every academic year, with documented checks that filtering works appropriately on all internet-connected devices in all relevant locations. This is a necessary and proportionate strengthening of online safeguarding duties. Current wording (“regularly review”) is too vague, allowing inconsistent or infrequent checks in some settings. Mandating an annual, documented review. The addition is practical and low-burden if systems are already compliant—many providers include annual audit tools/reports. It strengthens child protection without over-regulating, especially vital given AI’s rapid proliferation and child-on-child risks (e.g., sharing AI-generated intimate images). Suggestion for even stronger guidance: Cross-reference the need for reviews to include testing against emerging threats (e.g., generative AI bypass attempts) and staff training on interpreting monitoring alerts.”

Information security and access management

Proposal and rationale: We propose to change the wording in paragraph 170 and also add an additional paragraph on cyber security.

Cyber security is now recognised as a safeguarding concern, not just an IT concern. Schools and colleges hold sensitive personal data about children, including safeguarding records and health information. If this data is compromised through a cyber-attack, this can pose immediate risks to a child’s safety and wellbeing.

My response: “The change is welcome and overdue. Cyber security is no longer just an IT or administrative issue; breaches involving sensitive pupil data; especially safeguarding records, child protection files, health information (including mental health notes), attendance patterns, or family circumstances, can directly endanger children. By explicitly framing cyber security as a safeguarding concern, the update reinforces governing bodies’ and proprietors’ statutory duties under the Data Protection Act 2018/UK GDPR, Children Act 1989 (promoting welfare), and KCSIE’s broader requirement to keep children safe from harm (including digital harm). It rightly elevates responsibility from IT leads to senior leaders and DSLs, ensuring risk assessments, incident response plans, and staff training treat cyber threats as child protection matters. Cross-reference the need for annual cyber security reviews (similar to filtering/monitoring in para 166) and include a brief note on staff training to recognise phishing/social engineering attacks that could compromise safeguarding data. Overall, this is a positive, child-focused enhancement that strengthens holistic safeguarding in the digital age.”

Alternative provision (AP)

Proposal and rationale: We propose adding a paragraph between paragraphs 203 and 205, which sets out the department’s voluntary national standards for non-school alternative provision, along with guidance to support schools and local authorities in quality assuring providers.

Including reference to the voluntary national standards for non-school alternative provision in KCSIE helps strengthen safeguarding oversight for children educated outside traditional school settings. These standards provide a clear framework for quality assurance, supporting schools and local authorities in selecting safe and appropriate providers.

My response: “This reinforces schools’ safeguarding responsibilities. These standards provide a clear framework for quality assurance, covering safeguarding/welfare (Part 1: e.g., DSL arrangements, staff checks, risk assessments), health/safety (Part 2), admissions/support (Part 3), and education quality (Part 4). They help schools/LAs select safe providers for vulnerable children (e.g., excluded, medical needs, behaviour issues) who often face higher risks of harm, exploitation, or poor outcomes. Schools remain accountable for pupils in AP (Education Act 1996, Children Act 1989), and this addition prompts thorough checks (e.g., written confirmation of safeguarding, site visits) before commissioning. It prioritises child interests by ensuring AP is protective, not punitive; addressing gaps where unregulated settings have failed vulnerable children (e.g., serious case reviews on exploitation in AP). Even voluntary, inclusion in statutory KCSIE elevates oversight and supports transition to mandatory standards (planned legislation).In the child’s best interests, this safeguards those most at risk without mainstream access, promoting welfare over mere removal.”

My response: “These vulnerable pupils (e.g., with SEND, mental health, exclusion) often need tailored support but face risks in unregulated settings—standards address this with robust requirements for safeguarding (e.g., safer recruitment, behaviour policies, parental involvement), health/safety (e.g., site security, emergency procedures), and quality education (e.g., qualified staff, progress tracking). Schools/LAs gain a practical tool for vetting providers, ensuring placements meet individual needs and promote re-engagement/attendance (e.g., via admissions guidance). This aligns with child-centred interests under Working Together to Safeguard Children (2023), reducing harm from poor provision (e.g., isolation, exploitation). Voluntary status limits enforcement, but KCSIE reference encourages adoption, bridging to mandatory rules. Prioritising the child’s welfare: AP should rehabilitate, not warehouse, standards ensure safety, dignity, and outcomes. To enhance: Add explicit KCSIE requirements for regular monitoring visits and immediate withdrawal if standards fail, fully protecting these at-risk children.”

Medical conditions

Proposal and rationale: We have added a new paragraph (paragraph 243) which sets out guidance on ‘safeguarding children with medical conditions.’

My response: “The addition is positive and necessary. Children with medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, epilepsy, severe allergies, asthma, chronic pain, ETC) are often more vulnerable due to dependency on adults for care, potential for neglect (e.g., failure to administer medication), or exploitation (e.g., withholding treatment as punishment). Paragraph 243 outlines key indicators where medical needs intersect with safeguarding concerns. This clarifies the threshold for escalating from routine medical support to safeguarding action (e.g., early help, referral to children’s social care, or strategy discussion if risk of significant harm). It reinforces DSL responsibility to liaise with school nurses, health professionals, and parents while maintaining child-centred focus. The guidance helps schools distinguish legitimate medical management from neglect/abuse, reducing over- or under-reaction. Explicitly cross-reference the statutory duty to have Individual Healthcare Plans training for staff on condition-specific emergencies, and immediate escalation if a child’s condition deteriorates due to parental/carer failure. This would further strengthen child welfare without ambiguity.”

Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND)

Proposal and rationale: We have listened to previous stakeholder engagement which indicated that more was needed on additional barriers.

My response: “Expanding the list of additional barriers that children with SEND can face is helpful and aligns well with the child’s best interests. Children with special educational needs and disabilities are disproportionately vulnerable to safeguarding risks, including neglect, abuse, bullying, exploitation, and poor mental health outcomes. An expanded list could usefully include barriers such as:

Difficulty recognising or communicating abuse (e.g., non-verbal children, those with learning disabilities)

Higher risk of bullying, peer rejection, or child-on-child sexual violence

Dependency on carers/staff increasing risk of institutional or familial neglect/abuse

Intersection with other vulnerabilities (e.g., looked-after status, mental health needs, poverty)

Barriers to accessing help (e.g., assumptions that behaviours are “just part of their condition”)

Greater exposure to online harms if using assistive tech without adequate filtering/monitoring

Include a brief cross-reference to the SEND Code of Practice (section on safeguarding) and remind settings that Individual Education/Healthcare Plans must explicitly address safeguarding risks where relevant.”

Information Sharing

Proposal and rationale: We have strengthened guidance on the transfer of child protection files when a pupil moves to a new school or college. The update clarifies that the designated safeguarding lead (DSL) or a deputy should share any information indicating that a pupil may pose a risk to themselves or others, such as concerns about serious violence or harmful behaviours, with the receiving setting. In addition, we recommend that DSLs or a deputy from both settings have a direct conversation where there are significant issues or concerns, as good practice, to ensure continuity of safeguarding support.

My response: “I strongly support this clarification. It is essential for continuity of safeguarding that the outgoing DSL (or deputy) shares relevant information about risks to the pupil themselves or others when a child transfers schools/colleges. This includes concerns about serious violence, harmful sexual behaviour, child-on-child abuse, exploitation risks, or patterns indicating potential harm (e.g., weapon-carrying threats, coercive control, or radicalisation indicators). Current KCSIE already requires transfer of child protection files within 5 days (para 419 in 2025 version), but this explicit addition strengthens the duty to include risk-to-others information, aligning with Working Together to Safeguard Children (2023) and multi-agency expectations. The change is proportionate, child-centred, and compliant with Data Protection Act 2018/UK GDPR—sharing is lawful for safeguarding purposes. Suggestion: Add a reminder to document the rationale for sharing (or not sharing) specific information and to obtain parental consent where safe/appropriate, unless it would place the child at greater risk.”

My response: “I fully support recommending direct discussion between DSLs (or deputies) at the sending and receiving settings when there are significant concerns. Verbal handover is best practice for complex cases (e.g., serious violence, harmful sexual behaviour, exploitation, or high-risk mental health/suicide concerns) because: It allows real-time clarification, risk assessment updates, and immediate questions that written files may not convey. It builds professional relationships across settings, improving multi-agency working and continuity of support (e.g., agreeing on monitoring triggers, early help referrals, or behaviour plans). It reduces misinterpretation of records and ensures urgent safety measures (e.g., risk management plans) are in place from day one at the new school. The child’s best interests are served by this: swift, accurate information sharing protects the transferring pupil and prevents risks to new peers. To strengthen: Suggest the discussion occur before or immediately after transfer, with a brief note/record of key points agreed (without breaching confidentiality unnecessarily).”

Single Central Record

Proposal and rationale: In response to feedback from key stakeholders we have included an example single central record (SCR) template that meets the statutory requirements of KCSIE.

My response: “Yes, including an example single central record (SCR) template in KCSIE is very helpful. The SCR is a statutory requirement (Education Act 2002, Independent School Standards Regulations 2014, Non-Maintained Special Schools Regulations 2015) for recording pre-appointment vetting checks on all staff, supply teachers, volunteers, contractors, and others in regulated activity. Many schools/colleges struggle with format consistency, completeness, or audit readiness; especially smaller settings or those new to academisation. Suggestion for even greater value: Include guidance on digital vs paper SCRs, access controls (only authorised staff), annual audit requirements, and how to handle supply/agency staff (written confirmation from agencies). Also note retention periods.”

My response: “I am confident in responding to allegations against trainee teachers and understanding the roles involved. The draft KCSIE (Part four) already treats allegations against all adults working with children (including supply teachers, contractors, volunteers) under the same harm threshold and management procedures (paras 391–418 in 2025 version, with updates). The proposed addition explicitly includes “trainee teachers” throughout and inserts a new paragraph aligning procedures with those for supply/contracted staff. This removes any ambiguity: schools must follow the same steps—consider LADO referral (if harm threshold met), manage low-level concerns internally (if below threshold), involve the trainee’s provider/university for placement decisions, and ensure child safety (e.g., suspension from duties, risk assessment). Trainee teachers are not employees, so schools share responsibility with the training provider, but the school retains full safeguarding oversight on site.”

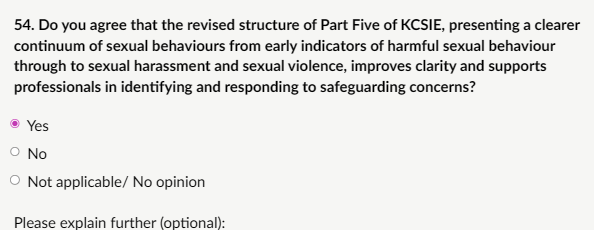

My response: “Yes, I agree that restructuring Part Five to present a clearer, progressive continuum; from early indicators of harmful sexual behaviour (HSB), through sexual harassment, to sexual violence, improves clarity and supports professionals. The sequential approach makes it easier for DSLs, teachers, and pastoral staff to locate relevant guidance quickly when behaviours escalate or are identified early. Current versions can feel disjointed; this logical flow enhances ease of reference, promotes consistent language, and encourages proactive identification of low-level concerning behaviours before they become serious incidents .This structure better supports child-centred safeguarding by emphasising early intervention, professional curiosity, and proportionate responses; key to preventing escalation and protecting both victims and children displaying HSB (who may themselves be victims of abuse or trauma). It aligns with Working Together to Safeguard Children (2023) and Ofsted expectations for robust handling of child-on-child abuse. The change is practical, evidence-informed, and strengthens overall safeguarding without adding complexity.”

My response: “Yes, aligning with frameworks like the Hackett Continuum significantly helps schools and colleges distinguish between developmentally inappropriate, problematic, and abusive sexual behaviours. The Hackett model (widely used in multi-agency safeguarding) provides a clear developmental lens: Developmentally inappropriate: behaviours outside age-expected norms but not necessarily harmful (e.g., curiosity in very young children). Problematic: behaviours causing concern or distress but not meeting abuse thresholds (e.g., persistent boundary-pushing). Abusive: behaviours involving coercion, lack of consent, power imbalance, or harm (meeting criminal/safeguarding thresholds). The revised Part Five structure, starting with early indicators and progressing to harassment/violence, embeds this continuum explicitly. This equips staff to: Avoid over- or under-reaction; Apply proportionate responses; Recognise that children displaying HSB may need safeguarding themselves It supports accurate risk assessment, reduces inconsistency, improves outcomes for all children involved, and strengthens compliance with statutory duties.”

- Understanding and responding to AI-generated child sexual abuse material and Financially motivated sexual extortion (FMSE)

My response: “Yes, adding these two specific links to Annex B is very helpful for schools and colleges. Both are real, fast-growing dangers to children in 2026: Pupils can now use free AI tools to make fake nude images or videos of classmates (deepfakes) this is criminal CSAM and child-on-child abuse. Sextortion (FMSE) leads to victims often feeling trapped and suicidal. Both resources are from trusted national sources (NCA/CEOP, IWF), evidence-based, and tailored for education settings. Placing them in Annex B; already the go-to reference for specific issues, makes them easily accessible during training, incident response, or policy reviews. This directly supports child safeguarding in emerging digital threat areas without adding length or complexity to the main guidance. Suggestion: Consider adding a brief one-line descriptor next to each link (e.g., “for recognising and reporting AI-generated CSAM and deepfakes”) to aid quick navigation.”

My response: “I fully support this requirement. Safeguarding must never be delayed because the DSL is absent (illness, leave, training, etc.). Children’s safety depends on immediate action when concerns arise, waiting even a day can allow harm to escalate (e.g., abuse, exploitation, suicide risk, serious violence). Suggestion: Add a short checklist in the annex: “Cover must include: named deputy/deputies, training records, contact details, escalation routes if deputy also unavailable, and annual review of arrangements.” This ensures consistency and auditability without adding burden.”

My response: “I strongly agree. Adding “skills and experience” to paragraph 125 (and reflected in Part two) is essential. The DSL role is the linchpin of safeguarding in every school/college, holding the position based only on status or seniority is not enough. Effective DSLs need: Practical experience dealing with real safeguarding cases (abuse, neglect, exploitation, mental health crises, child-on-child harm). Skills in risk assessment, multi-agency liaison (social care, police, health), record-keeping, staff support, and training delivery. Up-to-date knowledge of emerging threats (online harms, AI-generated CSAM, sextortion, serious youth violence). Ability to challenge poor practice and escalate without fear. “Skills and experience” makes clear that DSL appointment is not a tick-box role for a senior leader, it requires proven capability. This protects children by ensuring the person leading safeguarding is competent, not just available. It also supports recruitment and training planning. DSLs must have relevant safeguarding experience (ideally in child protection or similar) and demonstrable skills in case management.”

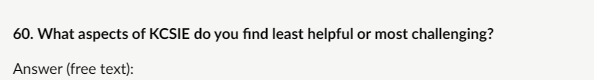

My response: “KCSIE is strongest where it prioritises clear, evidence-based child protection over ideology. Key helpful aspects include: Firm insistence on biological sex as immutable/binary for single-sex spaces (toilets age 8+, changing rooms/showers age 11+, boarding; paras 104–115, 191–196) no access to opposite-sex facilities for social transition, upholding Equality Act exceptions, School Premises Regulations 2012, and safeguarding duties (Children Act 1989). This protects privacy, dignity, and safety for all children, especially girls. Accurate biological sex recording/immediate parental involvement priority ensures transparency and family-led decisions. Robust single central record template. Annual filtering/monitoring reviews and cyber security as safeguarding addresses real digital threats (CSAM, sextortion, AI deepfakes). Explicit links to NCA/CEOP guidance on AI-generated CSAM and sextortion equips DSLs to respond swiftly to emerging online harms. Clear transfer of child protection files and direct DSL discussions on high-risk moves. These elements focus on real risks (abuse, exploitation, digital threats) with practical, enforceable steps exactly what effective safeguarding needs.”

My response: “The most challenging, problematic and least helpful aspect is any allowance for social transition (name/pronoun changes, even case-by-case; paras 251–268). This contradicts biological sex immutability, risks deceiving children/peers about unchangeable reality, and normalises a dangerous ideology. Cass Review (2024) views social transition as an active intervention with unknown long-term effects, limited evidence of benefits, and higher medical pathway risks pre-puberty. It can intensify distress, lead to “stealth” living, and misattribute trauma/neurodiversity as gender issues. Flexibility (e.g., alternatives in facilities/sports; creates loopholes for ideological exceptions, undermining single-sex protections and collective safety/privacy. This ambiguity risks inconsistent application, bullying, confusion, or safeguarding failures. Schools should prohibit all transition-related accommodations, no name/pronoun changes, no “identifying as” opposite sex, to safeguard every child from sex deception and ensure evidence-based, reality-grounded protection. Current flexibility is the biggest weakness and a huge safeguarding failure. This MUST be addressed.”

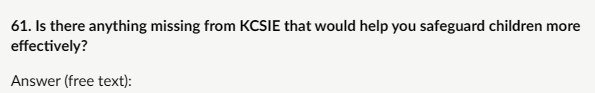

My response: “KCSIE must explicitly prohibit all forms of social transition in schools/colleges; no name/pronoun changes, no “identifying as” opposite sex, no stealth arrangements. This is essential to safeguard children from sex deception and ideological harm. Biological sex is immutable/binary (Equality Act 2010, Supreme Court rulings). Allowing any transition contradicts Cass Review evidence: social transition is non-neutral/active intervention and risks (e.g., increased medicalisation pre-puberty, stealth vulnerabilities, puberty anxiety). It can normalise mutable sex myths, confuse peers, enable bullying, and misdirect support from real issues (trauma, neurodiversity). Add mandatory: Zero school-facilitated transition; affirm biological sex only. Immediate parental notification of concerns (unless greater harm risk). Clinical referral without school involvement in identity affirmation. Explicit ban on any facility/sports exceptions that compromise single-sex rules. This protects all children’s welfare, privacy, and reality-based development, prioritising evidence over ideology. Current flexibility risks harm, no child should be forced to lie, remove the above for true safeguarding.”

Affluent neglect

‘Affluent neglect’ refers to situations whereby children from wealthy or privileged backgrounds experience neglect (particularly emotional or supervisory) despite having their material needs met.

My response: “Yes, ‘affluent neglect’ is a growing safeguarding concern and should be explicitly referenced and given guidance in KCSIE. This is increasingly reported in safeguarding literature and clinical settings. It is under-recognised because it does not fit traditional neglect stereotypes. Yet the impact is serious: attachment difficulties, poor emotional regulation, vulnerability to exploitation (grooming, county lines, online harms), and long-term mental health issues. KCSIE should include it across all settings, especially independent/private schools, where affluent neglect may be more prevalent. Guidance could cover: Indicators (e.g., frequent unaccompanied travel, excessive independence too young, emotional flatness, over-reliance on paid carers). Risk of assuming “they’re fine because they’re wealthy”. Need for DSLs to consider affluent neglect in referrals, early help, or multi-agency discussions. Links to mental health/safeguarding intersections (already in KCSIE) without over-medicalising. Explicit inclusion would ensure no child is overlooked due to socioeconomic bias, reinforcing that neglect is about emotional/supervisory failure, not just material deprivation.”

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

We welcome your views on how KCSIE can best support staff in understanding and responding to the evolving risks posed by AI technologies.

Technology continues to play a significant role in both safeguarding risks and opportunities. As AI tools become more widely used, particularly AI-powered chatbots, there is growing concern about their potential misuse in ways that could harm children and young people. These risks are evolving rapidly and may not yet be fully understood by all staff working in education settings.

My response: “Yes, KCSIE should include specific reference to the emerging safeguarding risks associated with artificial intelligence (AI). AI is already embedded in education (teacher planning tools, pupil-facing chatbots, image generators, research assistants) and the risks to children are real, serious, and evolving rapidly in 2026. However, AI also offers legitimate educational benefits: supporting lesson planning, accessibility (e.g., text-to-speech for SEND pupils), personalised learning, research summarisation, and creative tasks when used safely and ethically. Teachers and staff must be able to discern good from harmful uses, protect children from risks, and confidently teach about both the positive potential and the dangers of AI. Many remain unaware of risks or are overly restrictive, missing opportunities to prepare children for the real world. Balanced, explicit inclusion in KCSIE (Part Two, online safety, Annex B) ensures safeguarding remains number one while allowing responsible innovation. E.g. Explicit recognition of AI-generated CSAM/deepfakes alongside education-specific AI tools for teaching critical thinking, digital literacy, and responsible technology use.”

British Sign Language (BSL)

Currently KCSIE is not available in British Sign Language (BSL), we’re seeking views on whether there is a need for a BSL version to improve accessibility and equity in education settings.

My response: “Yes – Relying on written English (which may not be their first language), interpreters, or summaries risks misinterpretation of critical safeguarding obligations. BSL versions already exist for major statutory guidance (e.g., Working Together to Safeguard Children has BSL summaries/translations via DfE/partner channels; EHRC and Ofsted provide BSL resources). KCSIE is core statutory guidance; not providing it in BSL is inconsistent and fails to meet accessibility standards (Public Sector Bodies Accessibility Regulations 2018, WCAG 2.1 AA level for public sector digital content).A full BSL video translation (with on-screen text captions and clear signing) would be most effective, broken into short sections matching the document structure (Part One, Part Two, etc.) for easy reference. Even a summary BSL version covering must/should duties, key changes (e.g., gender questioning, AI risks, filtering), and Annexes would be valuable. This is low-cost, high-impact: improves inclusion, ensures all staff can meet statutory requirements confidently, and strengthens overall safeguarding culture by removing access barriers for Deaf professionals.”

Domestic abuse

Feedback from the wider sector has highlighted the need for clearer advice and strengthened language around Children Affected by Domestic Abuse (CADA).

My response: “I strongly agree that KCSIE should include more detailed information on Children Affected by Domestic Abuse (CADA), with clearer signposting to support services. Domestic abuse has profound, long-term impacts on children, even when they are not directly physically harmed. Children living with domestic abuse are at significantly higher risk of emotional harm, mental health difficulties, developmental delays, behavioural issues, poor school attendance, bullying perpetration/victimisation, and future involvement in abusive relationships or criminality. Explicit language would reinforce professional curiosity, reduce victim-blaming assumptions (e.g., “the child is just naughty”), and ensure schools support both the child and the non-abusive parent safely. It aligns with statutory duties to safeguard and promote welfare (Children Act 1989) and prevents children falling through gaps. Suggestion: Add -Definition and prevalence, Impact on children, Key indicators in school, Response pathways, Clear signposting to national/local services. This would be proportionate, evidence-based, and directly enhance child protection without lengthening the document excessively.”

Grooming Gangs

My response: “Yes, KCSIE should include clearer guidance on safeguarding risks associated with organised networks or grooming gangs, with direct links to relevant statutory guidance. Organised grooming gangs represent a serious, targeted form of child sexual exploitation involving multiple perpetrators, often exploiting vulnerabilities such as looked-after status, family breakdown, poverty, neurodiversity, or emotional neglect. Victims are groomed systematically, leading to repeated abuse, trafficking, and long-term trauma. Many cases have been under-reported or mishandled due to institutional failures. Clearer KCSIE guidance would help DSLs and staff: Recognise indicators, Understand multi-agency risks (e.g., fear of being labelled “racist” historically prevented reporting, Know when to refer to police, children’s social care, or relevant agencies. Explicit reference removes ambiguity and reinforces that child protection is paramount, regardless of perpetrator background. Guidance must explicitly state: safeguarding concerns must be raised and investigated without fear of being labelled racist or discriminatory. Child welfare comes first.”

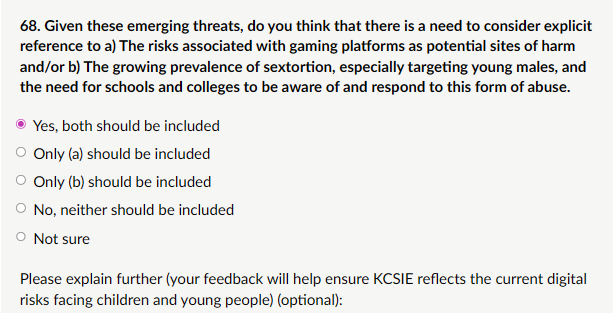

Gaming platforms

As children and young people increasingly engage with online platforms, the risks they face continue to evolve. While social media has long been recognised as a space where children may be targeted by offenders, there is growing concern about the use of gaming platforms as environments where grooming, exploitation, and contact by organised networks can occur.

In parallel, there is a rising trend in sextortion, particularly financially motivated sexual extortion, which disproportionately affects young males. Offenders often coerce victims into sharing explicit images and then demand money under threat of exposure. This form of abuse can have devastating emotional and psychological consequences.

My response: “Both gaming platforms and sextortion (especially financially motivated sexual extortion) must be explicitly referenced in KCSIE as emerging digital safeguarding risks. These threats are real, growing rapidly in 2026, and disproportionately affect children and young people in education settings. Gaming platforms (e.g., Roblox, Fortnite, Minecraft, Discord-integrated games, Call of Duty, GTA Online) are increasingly used for grooming, exploitation, and contact by organised networks. Sextortion (FMSE) is surging, with young males disproportionately affected (NCA/CEOP data 2025–2026 shows boys 13–17 as primary victims). Offenders coerce explicit images via gaming, social media, or dating apps, then demand money/crypto under threat of exposure to family/peers/school. Omitting them risks schools being under-prepared. Explicit inclusion (with signposting to CEOP/NCA resources) equips staff to protect children effectively, supports early identification, and aligns with Online Safety Act duties. Neither should be left vague; both warrant clear, mandatory reference to keep safeguarding current and robust.”

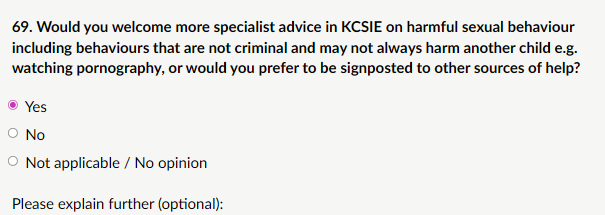

Harmful sexual behaviour (HSB)

Currently, KCSIE focuses on child-on-child harmful sexual behaviour (HSB). However, school staff may encounter situations involving HSB that is not criminal in nature and may not always harm another child e.g. a child watching pornography. These behaviours may not always result in direct harm but can still indicate underlying vulnerabilities or risks.

This consultation aims to ensure that school staff are equipped with the right knowledge and tools to respond confidently and appropriately to all forms of HSB, in line with best practice and evolving safeguarding needs.

My response: “Yes, I would welcome more specialist advice in KCSIE on harmful sexual behaviour (HSB), including behaviours that are not criminal and may not always directly harm another child (e.g., compulsive watching of pornography, excessive sexualised language, or solitary sexualised play that indicates distress or vulnerability). KCSIE already covers child-on-child sexual violence/harassment well in Part Five, but guidance on non-contact or solitary HSB is limited. Watching pornography is a key example with well-documented developmental harms in children and adolescents. Compulsive or early/secretive pornography use should trigger professional curiosity; not normalisation. More specialist advice embedded in KCSIE would ensure consistent, confident responses across all settings, prevent escalation, and safeguard children from both direct and indirect harms of HSB. Signposting alone risks inconsistent application.”

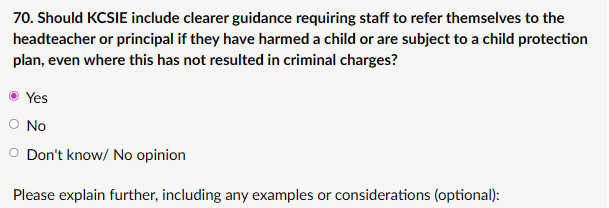

Self-Referral – Harm towards a child

It is our expectation that schools’ safeguarding policies and procedures would require individuals to disclose relevant information, including self-referral where they have harmed a child or are subject to safeguarding measures.

We are seeking views on whether Keeping Children Safe in Education (KCSIE) should provide clearer expectations around self-referral by staff. The current guidance requires staff to refer concerns about colleagues who may have harmed a child, but it is less explicit about situations where staff themselves may have harmed a child or are subject to safeguarding measures, such as a child protection plan.

We want to understand whether stakeholders believe KCSIE should make this expectation clearer.

My response: “Yes, KCSIE should include clearer guidance. Safeguarding is about protecting children first; staff who have harmed a child (physically, emotionally, sexually, through neglect, or via any form of abuse) or are themselves under a child protection plan pose an unacceptable ongoing risk in any role involving children. Current guidance rightly requires colleagues to report concerns about others (Part Four, harm threshold), but it is silent or unclear on self-disclosure. This gap allows potential abusers to continue working with children undetected if no external allegation is made. The expectation should be framed as a professional duty: staff must disclose to the headteacher/principal any personal involvement in harming a child or being subject to safeguarding measures (including their own family). This strengthens safeguarding culture; transparency protects children more effectively than silence. No child should be exposed to avoidable risk because staff obligations are unclear.”

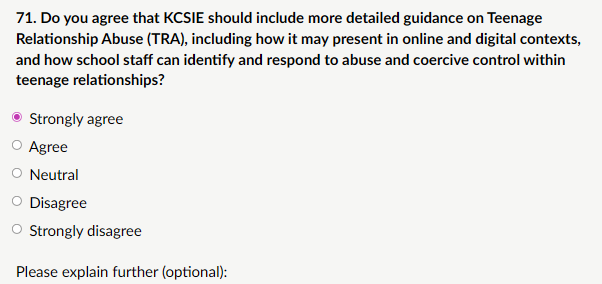

Teenage relationship abuse

Currently, KCSIE includes limited wording on teenage relationship abuse, despite growing evidence of its prevalence among young people. With high and increasing rates of abuse in teenage relationships, especially online and through technology, teachers and school staff may require clearer guidance on how teenage relationship abuse may present, how children may be abused or controlled by their partners, and what interventions are appropriate.

While KCSIE outlines signs of harm in the context of intra-familial domestic abuse, it does not currently support school staff in recognising or responding to abuse within teenage relationships.

My response: “Teenage relationship abuse is widespread and rising, with recent UK data (2024–2026) showing 20–30% of young people aged 13–18 experiencing controlling, coercive, emotional, physical, or sexual abuse from a partner or ex-partner. Current KCSIE covers intra-familial domestic abuse well but is silent or limited on peer/teenage intimate partner abuse. This gap leaves staff under-equipped to recognise signs. Without explicit guidance, staff may dismiss these as “normal teenage drama” or “puppy love,” delaying intervention and allowing abuse to worsen (e.g., leading to mental health crises, school refusal, or escalation to serious violence). Stronger KCSIE guidance should cover: Definition and prevalence of TRA (including digital forms); Key indicators; How to respond, early help referrals, specialist services. Links to RSHE curriculum for prevention (healthy relationships, consent, digital boundaries); and Multi-agency pathways (police for criminal offences, social care for welfare concerns). Teenagers deserve the same protection from intimate partner abuse as adults.”

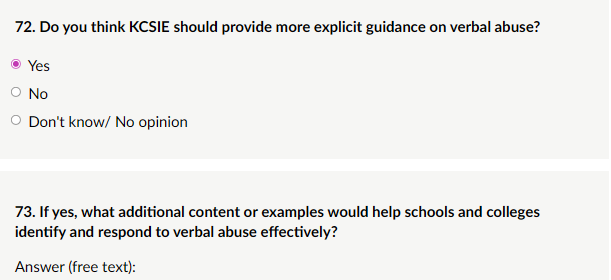

Verbal abuse

KCSIE sets out different forms of abuse, including physical, sexual, emotional, and neglect. While verbal abuse is referenced within emotional abuse, we are interested in whether KCSIE should say more about verbal abuse as a distinct safeguarding concern. This could include clearer examples of harmful language, persistent derogatory remarks, or threats, and how these can impact a child’s wellbeing and safety.