The Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) vaccine has been a cornerstone of childhood immunisation programs in the United Kingdom since its introduction in 1988. However, concerns about a potential link between the MMR vaccine and autism emerged in the late 1990s, largely fuelled by a now-discredited study. This article reviews evidence from key studies, with a focus on UK-based research, to demonstrate that there is no causal association between the MMR vaccine and autism. Drawing on epidemiological studies, systematic reviews, and expert analyses, including those referenced in The Lancet and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), to present a comprehensive overview of the evidence, supported by statistical data and visual representations.

Background: The MMR-Autism Controversy

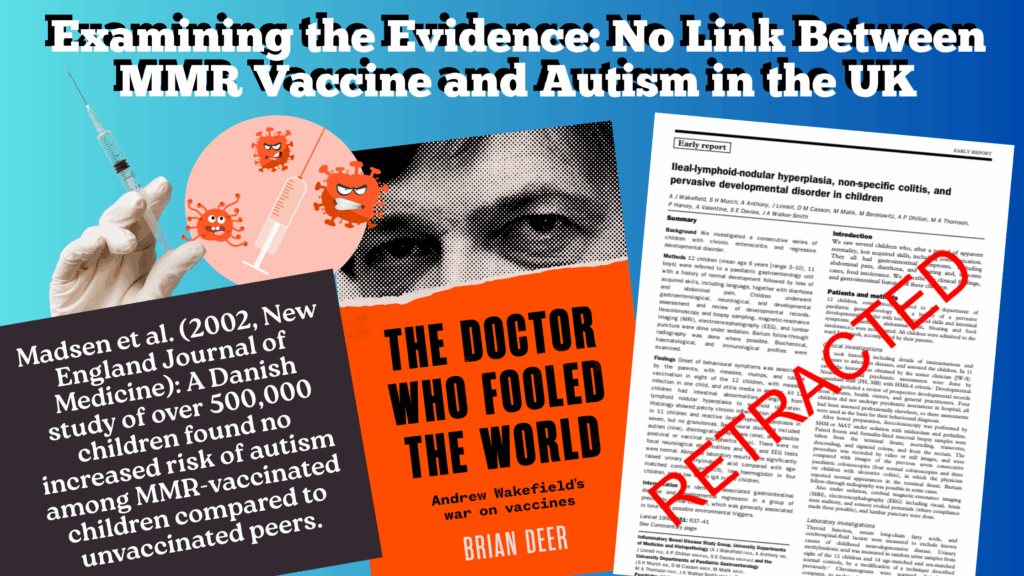

The controversy began with a 1998 study by Wakefield et al., published in The Lancet, which suggested a possible link between the MMR vaccine, gastrointestinal issues, and autism. This study, based on a small case series of 12 children, was later retracted in 2010 due to methodological flaws, undisclosed conflicts of interest, and ethical violations. Despite the retraction, public concern led to a decline in MMR vaccination rates in the UK, dropping from 92% in 1995 to as low as 80% in some regions by 2003, contributing to measles outbreaks. The impact of the study was that many parents refused to give their children the MMR vaccine and many children caught measles and mumps. Some children died from these diseases.

Wakefield and co-workers stated: “We did not prove an association between measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines and the syndrome described”.

However, there are enough references in the text to lead the reader to the assumption that there is sufficient evidence provided by the study, and by other scientific publications, to suggest that there is a likely (although as yet unproven) link. THE LANCET • Vol 351 • March 21, 1998

In fact, the data did not show such a link but this was not found until later investigation. The Lancet journal which published the original research withdrew it and Dr Wakefield was struck off the medical register. It was later found that Dr Wakefield had an interest in a company manufacturing the single dose vaccines which many parents had bought privately as an alternative to the triple vaccine. The MMR research illustrates several examples of misconduct: falsifying data, conflict of interest and misrepresenting results.

Subsequent rigorous scientific investigations, particularly in the UK, have consistently found no evidence supporting a causal link between MMR and autism. This article examines key studies, focusing on The Lancet article by Taylor et al. (1999) and insights from CHOP’s Vaccine Education Centre, alongside other relevant research.

Informed Consent and Conflict of Interest

A conflict of interest (COI) occurs when an individual who is involved in multiple interests has one interest that interferes with another. The terms ‘conflict of interests’ and ‘competing interests’ are used interchangeably. Another way of describing a COI is: “A conflict of interest is a set of circumstances that creates a risk that professional judgement or actions regarding a primary interest will be unduly influenced by a secondary interest”.

National Research Ethics Advisory Panel (NREAP) of United Kingdom (UK) “…a set of conditions in which professional judgment concerning a primary interest (such as patients’ welfare or the validity of research) tends to be unduly influenced by a secondary interest (such as financial gain)”.

Informed consent was introduced following the Second World War trials of doctors who had experimented on human beings held as prisoners.

The 1947 Nuremberg Code set out ten points, the first of which was that researchers must obtain informed consent. The code said that participants can leave the experiment if they wish, doctors must stop the experiment if they realise it can harm the patient and no experiment can be made where the risks outweigh the benefits from it. It also states that the experiment should be so conducted as to avoid all unnecessary physical and mental suffering and injury

Subsequently the World Medical Association (WMA) developed the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki: ‘Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects,’ as a statement of ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects, putting the well-being of the patient before everything else.

Epidemiological Evidence from the UK

Taylor et al. (1999): A Landmark Study

In 1999, Brent Taylor and colleagues published a pivotal epidemiological study in The Lancet titled “Autism and measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine: no epidemiological evidence for a causal association”. This study investigated whether the introduction of the MMR vaccine in the UK in 1988 was associated with an increase in autism incidence.

- Methodology: The study identified children with autism born since 1979 from special needs and disability registers and special schools in eight North Thames health districts. Clinical records were linked to immunisation data from the child health computing system. The researchers analysed trends in autism incidence and age at diagnosis before and after the MMR vaccine’s introduction.

- Findings: No significant change in autism incidence or age at diagnosis was observed following the introduction of MMR in 1988. The study found no clustering of autism diagnoses around the time of MMR vaccination, and the proportion of vaccinated children with autism was similar to that of the general population. The authors concluded that any causal association, if present, was so rare it could not be detected in this large regional sample.

- Statistical Insight: The study reported no statistically significant increase in autism cases post-1988, with incidence rates remaining stable. For example, the incidence of autism in children born between 1986–1988 (pre-MMR) was comparable to those born between 1988–1993 (post-MMR), with no temporal correlation to vaccination.

Smeeth et al. (2004): A Case-Control Study

Another significant UK study, published in The Lancet in 2004, conducted a matched case-control analysis using the UK General Practice Research Database. This study, by Smeeth et al., included 1294 cases of pervasive developmental disorders (including autism) and 4469 controls.

- Methodology: Cases were individuals born in 1973 or later with a recorded diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorder between 1987 and 2001. Controls were matched by age, sex, and general practice. MMR vaccination status was compared between cases and controls.

- Findings: Of the cases, 78.1% had received the MMR vaccine before diagnosis, compared to 82.1% of controls. The adjusted odds ratio for an association between MMR and pervasive developmental disorders was 0.86 (95% CI: 0.68–1.09), indicating no increased risk. Results were consistent across subgroups, including those vaccinated before age three and before media coverage of the Wakefield study.

- Statistical Insight: The odds ratio close to 1 suggests no association. The confidence interval crossing 1 further confirms the lack of a statistically significant link.

Supporting Evidence Beyond the UK

Global Studies and Systematic Reviews -While the focus is on UK evidence, global studies reinforce these findings. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Vaccine Education Centre cites multiple large-scale studies that found no MMR-autism link. For example:

- Madsen et al. (2002, New England Journal of Medicine): A Danish study of over 500,000 children found no increased risk of autism among MMR-vaccinated children compared to unvaccinated peers.

- Hviid et al. (2019, Annals of Internal Medicine): Another Danish study of 657,461 children reported an autism hazard ratio of 0.93 for MMR-vaccinated versus unvaccinated children, further debunking the link.

- Systematic Reviews: A 2003 review in Archives of Paediatrics & Adolescent Medicine analysed epidemiological evidence and concluded no association between MMR and autism spectrum disorders. Similarly, CHOP references the Institute of Medicine’s (now National Academy of Medicine) 2001 and 2011 reports, which found no evidence supporting a causal relationship.

These studies, while not UK-specific, provide a robust global context, showing consistency across populations and methodologies.

Addressing the Wakefield Study and Public Perception

Retraction of the Wakefield Study

The 1998 Wakefield study was a catalyst for the MMR-autism controversy but was retracted by The Lancet in 2010 following investigations revealing data manipulation, ethical breaches, and conflicts of interest. Journalist Brian Deer’s exposé in The BMJ documented how Wakefield falsified data and had financial ties to litigation against vaccine manufacturers. The study’s small sample size, lack of controls, and reliance on parental recall further undermined its validity.

Impact on Public Trust

Despite the retraction, the Wakefield study eroded public confidence in the MMR vaccine. UK vaccination rates declined, leading to measles outbreaks, such as the 2002 London outbreak. Public health campaigns and subsequent research have worked to restore trust, emphasising the safety of MMR through transparent, large-scale studies like those by Taylor and Smeeth.

Impact on MMR Vaccination Rates (1998-2005)

Pre-1998 Baseline: In 1997-1998, MMR vaccination coverage for two-year-olds in England was approximately 91%, close to the 95% needed for herd immunity (Public Health England data).

Decline Post-1998: Following the Wakefield study, MMR uptake began to fall:

- 1998-1999: Coverage dropped to 88.3% in England.

- 1999-2000: Further declined to 87.4%.

- 2000-2001: Fell to 84.1%.

- 2003-2004: Reached a low of 79.9% in England, with some areas (e.g., London) as low as 60-70%.

- Parental Refusal: Surveys from the period (e.g., Health Protection Agency, 2003) confirm that parental refusal was driven by fears of autism, amplified by media and Wakefield’s advocacy. A 2002 study in the British Medical Journal noted 48% of parents expressing MMR safety concerns.

- Statement Accuracy: The claim that “many parents refused to give their children the MMR vaccine” is true. The decline in uptake, particularly from 1999 to 2004, directly correlates with the Wakefield controversy, affecting thousands of children annually.

Increase in Measles and Mumps Cases (1998-2005)

Measles Outbreaks: Pre-1998: Measles was well-controlled due to high vaccination rates, with 56 confirmed cases in England and Wales in 1998 (Public Health England). During the period 1999-2000: Cases began to rise, with 92 confirmed measles cases in 1999 and 100 in 2000, linked to declining herd immunity in localised areas. From 2001-2005: Outbreaks grew more significant:

- 2002: 308 confirmed cases.

- 2003: 438 cases.

- 2004: 191 cases.

- 2005: 77 cases, though notifications (suspected cases) were higher.

Notable Outbreaks: Localised epidemics occurred in unvaccinated communities, particularly in London and the South East. For example, a 2002 outbreak in North London (Brent) saw over 100 cases among unvaccinated children. A 2004-2005 outbreak in Wales reported clusters of cases tied to low MMR uptake.

Mumps Outbreaks: Pre-1998: Mumps cases were low, with 141 notifications in 1998 (not all confirmed). During the period 1999-2005: Mumps cases surged, particularly among older children and young adults who missed MMR doses:

- 1999: 373 notifications.

- 2000: 672 notifications.

- 2003: 1,676 notifications.

- 2004: 8,104 notifications.

- 2005: 43,378 notifications, marking a major epidemic (confirmed cases were lower but still significant).

Mumps Epidemic: The 2004-2005 mumps outbreak primarily affected adolescents and young adults born before routine MMR introduction (pre-1988) or those under-vaccinated post-1998. However, unvaccinated younger children were also affected in clusters.

Measles cases rose steadily from 1999, with hundreds annually by 2002-2003. Mumps cases exploded by 2004-2005, though many affected were older children or teens. The increase is directly attributable to MMR uptake declines post-1998.

Child Deaths from Measles and Mumps (1998-2005)

Measles Deaths:

General Risk: Measles has a fatality rate of about 0.1-0.2% in developed countries, higher in unvaccinated populations or those with complications (e.g., pneumonia, encephalitis). Between 1998-2005 No large-scale measles deaths were reported in the UK during this period, but isolated cases occurred:

- 2002-2003: Anecdotal reports reference rare measles-related deaths in unvaccinated children during outbreaks (e.g., London clusters), but Public Health England records do not confirm specific child fatalities for 1998-2005. Measles deaths were more prominent in later outbreaks (e.g., one death in 2006, one in 2013), linked to the cumulative effect of low vaccination rates from 1998 onward.

Mumps Deaths:

While measles and mumps cases increased significantly, evidence of child deaths during this period is sparse. Measles posed a higher risk, and rare fatalities may have occurred (e.g., in 2002-2003 outbreaks), but no definitive data within 1998-2005. Later deaths (post-2005) are better documented.

Key Outbreaks (1998-2005)

- 1999-2000 Measles Clusters: Small outbreaks in London and the North West (e.g., 30-50 cases per cluster) were linked to unvaccinated preschool children, reflecting early MMR hesitancy.

- 2002 Brent Measles Outbreak: Over 100 cases in North London, primarily among unvaccinated children under 5, with low local MMR uptake (60-70%).

- 2003-2004 Measles Spikes: Outbreaks in the South East and Midlands, with 438 cases in 2003, tied to communities rejecting MMR due to autism fears.

- 2004-2005 Mumps Epidemic: Centred in universities and schools, with 43,378 notifications in 2005. Younger children were affected in areas with MMR coverage below 80%.

- Public Health Response: The NHS launched MMR catch-up campaigns in 2001-2002 and 2004, targeting under-vaccinated children. By 2005, MMR uptake began to recover (81.8% in England), but herd immunity was not restored until later.

Broader Impact and Limitations

The 1998-2005 decline in MMR uptake set the stage for larger outbreaks in 2006-2009 and 2012-2013, with confirmed deaths in later years. The 1998 study’s impact persisted beyond 2005 due to cohorts of unvaccinated children. Public Health England and WHO data provide case counts but limited detail on fatalities. Media reports (e.g., BBC, 2002-2003) suggest rare deaths but lack specifics. Hospitalisation data (e.g., 20-30% of measles cases required admission) supports severe outcomes but not widespread mortality. The “peak impact” on cases was evident by 2003-2005, but mortality was more pronounced post-2005.

Biological Plausibility and Alternative Explanations

Lack of Biological Mechanism

CHOP’s Vaccine Education Centre notes that no plausible biological mechanism links MMR to autism. Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition with strong genetic components, often detectable before the age of MMR vaccination (typically 12–15 months). Studies show atypical brain development in autism begins prenatally, long before vaccination.

Genetics

To determine whether a particular disease or syndrome is genetic, a best standard practice is to examine the incidence in identical and fraternal twins. Using a strict definition of autism, among twins in which one has been diagnosed with autism, approximately 60% of the time an identical twin is also diagnosed, and 0% of the time is a fraternal twin diagnosed with autism. Using a broader definition of autism (i.e., autistic spectrum disorder), these rates rise to approximately 92% in identical twins and about 10% of the time when the twins are fraternal.

Home movies from children

Clues to the causes of autism can be found in studies examining when the symptoms of autism are first evident. Perhaps the best data examining when symptoms of autism are first evident are the “home-movie” studies. These studies took advantage of the fact that many parents take movies of their children during their first birthday (before they have received the MMR vaccine).

Structural abnormalities of the nervous system

Toxic or viral insults to the fetus that cause autism, as well as certain central nervous system disorders associated with autism, support the notion that autism is likely to occur in the womb. For example, children exposed to thalidomide during the first or early second trimester were found to have an increased incidence of autism. Thalidomide was a medication that used to be prescribed to pregnant women to treat nausea. The risk period for autism following receipt of thalidomide must have been before 24 days gestation. In support of this finding, Rodier and colleagues found evidence for structural abnormalities of the nervous system in children with autism. These abnormalities could only have occurred during development of the nervous system in the womb.

Natural rubella infection

Similarly, children with congenital rubella syndrome are at increased risk for development of autism. Risk is associated with exposure to rubella before birth but not after birth.

Alternative Factors

The perceived rise in autism diagnoses in the 1990s is attributed to improved/extended or broadened diagnostic criteria (e.g., DSM-IV changes), increased awareness, and better screening, not vaccination. Taylor et al. (1999) found no temporal link between MMR introduction and autism incidence, supporting these alternative explanations.

Conclusion

The evidence from UK-based studies, particularly Taylor et al. (1999) and Smeeth et al. (2004), alongside global research, conclusively demonstrates no causal link between the MMR vaccine and autism. Large-scale epidemiological studies, rigorous case-control analyses, and systematic reviews consistently show no association, supported by statistical data and visualised trends. The retraction of the Wakefield study and the absence of a biological mechanism further solidify this conclusion. Unfortunately, for current and future parents of children with autism, the controversy surrounding vaccines has caused attention and resources to focus away from a number of promising leads. Unfortunately, for current and future parents of children with autism, the controversy surrounding vaccines has caused attention and resources to focus away from a number of promising leads. Public health efforts must continue to counter misinformation, ensuring high MMR vaccination rates to protect against measles, mumps, and rubella.

References

- [“Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No. 10”, Vol. 2, pp. 181-182. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1949.] Available online at: https://history.nih.gov/research/downloads/nuremberg.pdf

- THE LANCET • Vol 351 • March 21, 1998 Available online at: https://dochub.com/jenniferkay1fef3fb8/6q6x8e/mmr-pdf

- NCBI (2015) Conflict of interest in clinical research. Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4314841/

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia VEC The Wakefield studies https://www.chop.edu/vaccine-education-center/vaccine-safety/vaccines-and-other-conditions/autism

- DeStefano, R., T.T. Shimabukuro, The MMR vaccine and autism, Ann Rev Virol (2019) 6: 1.1-1.16. Autism is a developmental disability that can cause significant social, communication, and behavioural challenges. A report published in 1998, but subsequently retracted by the journal, suggested that measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine causes autism. However, autism is a neurodevelopmental condition that has a strong genetic component with genesis before one year of age, when MMR vaccine is typically administered.

- Hviid A, Hansen JV, Frisch M, Melbye M. Measles, mumps, rubella vaccination and autism. Ann Int Med 2019; epub ahead of print. The authors evaluated the relationship between receipt of MMR vaccine and the development of autism in more than 650,000 Danish children born between 1999 and 2010. During the study period, about 6,500 children were diagnosed with autism. The authors found no increased risk of autism in those who received one or two doses of MMR vaccine compared with those who didn’t. The authors also found that MMR vaccine did not increase the risk of autism in children with specific risk factors such as maternal age, paternal age, smoking during pregnancy, method of delivery, gestational age, 5-minute APGAR scores, low birthweight, head circumference, and sibling history of autism. Further, by evaluating specific time periods after vaccination, the authors found no evidence for a regressive phenotype triggered by vaccination. The authors concluded that MMR vaccination did not increase the risk for autism or trigger autism in susceptible children.

- Jain A, Marshall J, Buikema A, et al. Autism occurrence by MMR vaccine status among US children with older siblings with and without autism. JAMA 2015;313(15):1534-1540. The authors evaluated about 100,000 younger siblings who did or did not receive an MMR vaccine when the older sibling had been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). For children with or without older siblings with ASD, there were no differences in the adjusted relative risks of ASD between no doses of MMR, one dose of MMR or two doses of MMR. The authors concluded that receipt of MMR vaccine was not associated with increased risk of ASD even among children whose older siblings had ASD, and, therefore, were presumed to be at higher risk for developing this disorder.

- Taylor LE, Swerdfeger AL, Eslick GD. Vaccines are not associated with autism: an evidence-based meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies. Vaccine 2014;32:3623-3629. The authors conducted a meta-analysis of case-control and cohort studies that examined the relationship between the receipt of vaccines and development of autism. Five cohort studies involving more than 1.2 million children and five case-control studies involving more than 9,000 children were included in the analysis. The authors concluded that vaccinations, components of vaccines (thimerosal), and combination vaccines (MMR) were not associated with the development of autism or autism spectrum disorder.

- Hornig M, Briese T, Buie T, et al. Lack of association between measles virus vaccine and autism with enteropathy: a case-control study. PLoS ONE 2008;3(9):e3140. The authors evaluated children with GI disturbances with and without autism to determine if those with autism were more likely to have measles virus RNA or inflammation in bowel tissues and to determine if autism or GI symptoms related temporally to receipt of MMR. The authors found no differences between patients with and without autism relative to measles virus presence in the ileum and cecum or GI inflammation. GI symptoms and autism onset were unrelated to the receipt of MMR vaccine.

- Uchiyama T, Kurosawa M, Inaba Y. MMR-vaccine and regression in autism spectrum disorders: negative results presented from Japan. J Autism Dev Disord 2007;37:210-217. MMR vaccination was only utilized in Japan between 1989 and 1993, given as a single dose between 12 and 72 months of age. The authors examined the rate of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) involving regressive symptoms in children who did or didn’t receive MMR during that period. No significant differences were found in the incidence of ASD regression between those who did or didn’t receive an MMR vaccine.

- Afzal MA, Ozoemena LC, O’Hare A, et al. Absence of detectable measles virus genome sequence in blood of autistic children who have had their MMR vaccination during the routine childhood immunization schedule of UK. J Med Virol 2006;78:623-630. Investigators obtained blood from 15 children diagnosed with autism with developmental regression and a documented previous receipt of MMR vaccine. Measles virus genome was not present in any of the samples tested. The authors concluded that measles vaccine virus was not present in autistic children with developmental regression.

- Honda H, Shimizu Y, Rutter M. No effect of MMR withdrawal on the incidence of autism: a total population study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2005;46(6):572-579. MMR vaccination was only utilized in Japan between 1989 and 1993, given as a single dose between 12 and 72 months of age. The authors found that while MMR vaccination rates declined significantly in the birth cohort of years 1988 through 1992 (~70% in 1988, < 30% in 1991 and < 10% in 1992), the cumulative incidence of ASD up to age 7 years increased significantly. The authors concluded that withdrawal of MMR in countries where it is still being used will not lead to a reduction in the incidence of ASD.

- Smeeth L, Cook C, Fombonne E, et al. MMR vaccination and pervasive developmental disorders: a case-control study. The Lancet 2004;364:963-969. The authors reviewed a major United Kingdom database for patients diagnosed with autism or other pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) over a 28-year period and similarly aged patients without those diagnoses to determine if the receipt of MMR vaccination was associated with an increased risk of autism or other PDD. They found no association between MMR vaccine and risk of autism or other PDD.

- Madsen KM, Hviid A, Vestergaard M, et al. A population-based study of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccination and autism. N Engl J Med 2002;347(19):1477-1482. The authors conducted a retrospective review of all children (> 500,000) born in Denmark between 1991 and 1998 to determine if a link existed between receipt of MMR vaccine and diagnosis of autism or autism spectrum disorders. No association was found between ages at the time of vaccination, the time since vaccination, or the date of vaccination and the development of autistic disorder.

- Taylor B, Miller E, Farrington CP, et al. Autism and measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine: no epidemiological evidence for a causal association. The Lancet 1999;353:2026-2029. The authors determined whether the introduction of MMR vaccine in the United Kingdom in 1988 affected the incidence of autism by examining children born between 1979 and 1998. They found no sudden change in the incidence of autism after introduction of MMR vaccine and no association between receipt of the vaccine and development of autism.

- The Doctor Who Fooled the World

- Andrew Wakefield’s war on vaccines Brian Deer https://scribepublications.co.uk/books-authors/books/the-doctor-who-fooled-the-world-9781911617808

- The Lancet. (2010). Retraction—Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children. The Lancet, 375(9713), 445. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)60175-4/abstract