The British political system is one of the oldest and most influential in the world, evolving over centuries from absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary democracy. Its development reflects a gradual shift in power from the Crown to the people, shaped by key historical events, legal documents, and societal changes. Today, the UK operates a complex system of governance, with elections and voting at its core. This article explores its origins, evolution, and current mechanics.

Early Foundations: Monarchy and Magna Carta

The roots of the British political system lie in the Anglo-Saxon period, when tribal kings ruled with the advice of councils like the Witan. After the Norman Conquest in 1066, William the Conqueror centralised power, establishing a feudal system where the monarch held supreme authority. However, this power was first challenged in 1215 with the signing of the Magna Carta.

Magna Carta, meaning “Great Charter” in Latin, is a landmark document. Forced upon King John by rebellious barons, this document limited royal authority, established the principle that no one is above the law, and laid the groundwork for parliamentary governance. In 2015 the Houses of Parliament, along with the people of the UK, commemorated 800 years since the sealing of Magna Carta (1215).

The original Magna Carta was reissued and revised by King Henry III in 1216, 1217, and 1225, with the 1225 version becoming the most influential.

There are 63 clauses in Magna Carta. For the main part, the clauses do not deal with legal principles but instead relate to the regulation of feudal customs and the operation of the justice system. There are clauses on the granting of taxes, towns and trade, the extent and regulation of the royal forest, debt, the Church and the restoration of peace. Only four of the 63 clauses in Magna Carta are still valid today – 1 (part), 13, 39 and 40. Of enduring importance to people appealing to the charter over the last 800 years are the famous clauses 39 and 40:

A right to due legal process (clauses 39 and 40 in the 1215 charter, clause 29 in the 1297 statute). Imprisonment, &c. contrary to Law. Administration of Justice. NO Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor [condemn him,] but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the Land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.

The “ancient liberties” of the City of London (clause 13 in the 1215 charter, clause 9 in the 1297 statute) Liberties of London, &c. – THE City of London shall have all the old Liberties and Customs [which it hath been used to have]. Moreover We will and grant, that all other Cities, Boroughs, Towns, and the Barons of the Five Ports, and all other Ports, shall have all their Liberties and free Customs.

Confirmation of Liberties. the freedom of the Church of England (clause 1) FIRST, We have granted to God, and by this our present Charter have confirmed, for Us and our Heirs for ever, that the Church of England shall be free, and shall have all her whole Rights and Liberties inviolable. We have granted also, and given to all the Freemen of our Realm, for Us and our Heirs for ever, these Liberties under-written, to have and to hold to them and their Heirs, of Us and our Heirs for ever.

These clauses remain law today, and provided the basis for important principles in English law developed in the fourteenth through to the seventeenth century, and which were exported to America and other English-speaking countries. Their phrasing, ‘to no one’ and ‘no free man’ gave these provisions a universal quality that is still applicable today in a way that many of the clauses relating specifically to feudal custom are not.

The Birth of Parliament

By the 13th century, the concept of a parliament emerged. In 1265, Simon de Montfort summoned a council including knights and burgesses alongside barons, an early precursor to the House of Commons. Simon De Montfort’s Parliament was the first instance of a parliament in which representatives from towns and the shires were summoned together to discuss matters of national concern. This Parliament is seen as the earliest forerunner of the modern Parliament because of its inclusion of both knights and burgesses, for a reason other than the granting of taxation. This broadened the types of people represented at a high level who were participating in affairs of the nation.

The Model Parliament of 1295 under Edward I further formalised this, inviting representatives from various classes. It included not only archbishops and bishops but also archdeacons and one proctor for each cathedral and two for each diocese, marking the first time the lower orders of clergy were represented. In addition, there were two knights from each shire, two citizens from each city, and two burgesses from each borough. Seven earls and 42 barons were also summoned. Initially, Parliament’s role was advisory, approving taxes and petitioning the king, but its influence grew over time.

The 14th and 15th centuries saw the division into two houses: the House of Lords (nobility and clergy) and the House of Commons (elected representatives). Lords Temporal attend the House of Lords on an almost entirely hereditary basis. ‘Peers’, as they became known, are accountable to each other and divide into five ranks: duke, marquess, earl, viscount and baron.

The Struggle for Power: Civil War and the Glorious Revolution

As a result of Henry VIII’s break from Roman Catholicism during the 16th Century and the dissolution of the monasteries, the number of abbots attending the House of Lords is reduced. By the end of the reign of Elizabeth I, there are no abbots in the House of Lords and 26 Church of England bishops. During this period, the Lords Temporal form a majority for the first time.

The 17th century was a turning point. Tensions between King Charles I and Parliament over taxation and authority led to the English Civil War (1642–1651). Parliament’s victory, under Oliver Cromwell, briefly abolished the monarchy, establishing a republic (the Commonwealth).

The Glorious Revolution of 1688–1689 marked a decisive shift: King James II was deposed, and William III and Mary II accepted the throne under the Bill of Rights 1689, which entrenched parliamentary supremacy and individual rights, it establishes Parliament’s authority over the king. The Glorious Revolution established a constitutional monarchy, where the rights of citizens were protected. The Glorious Revolution led to the Toleration Act of 1689, which granted religious freedom to nonconformist Protestants, though not to Catholics. The revolution had a complex and sometimes bloody impact on Scotland and Ireland, with Jacobite uprisings and the establishment of a Presbyterian church in Scotland.

The Rise of Constitutional Monarchy and Party Politics

The 18th and 19th centuries saw the monarchy’s role diminish to more of a symbolic one, with real power resting in Parliament. Political parties also took shape: the Whigs (later Liberals) and Tories (later Conservatives) dominated, formalising the two-party system. The office of Prime Minister emerged informally under Robert Walpole (1721–1742), evolving into the head of government. His political rise was swift. He became Secretary at War in 1708 and Treasurer of the Navy in 1710 to 1711. However, his involvement in the prosecution of Tory preacher Henry Sacheverell had consequences. The Tory government elected in 1710 targeted Walpole: he was found guilty of corruption and briefly imprisoned in the Tower of London in 1712, becoming a Whig martyr in the process. The accession of the Hanoverian King George I in 1714 returned the Whigs to power. Walpole was appointed First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1715, but followed his brother-in-law and political mentor, Charles, 2nd Viscount Townshend, into opposition in 1717 when the Whigs split. Traditionally regarded as the first Prime Minister, Walpole lived in 10 Downing Street from 1735 having insisted that it become the residence of the First Lord of the Treasury, rather than being given to him personally. Royal support helped him survive a serious crisis over his tax plans in 1733, but in 1742 a combination of opposition from the Prince of Wales and a deteriorating foreign political situation forced his resignation.

The Great Reform Act of 1832 expanded voting rights, addressing inequalities in representation, though suffrage remained limited to propertied men, voting rights were given to the property-owning middle classes in Britain. However, many working men were disappointed that they could not vote.

Chartists

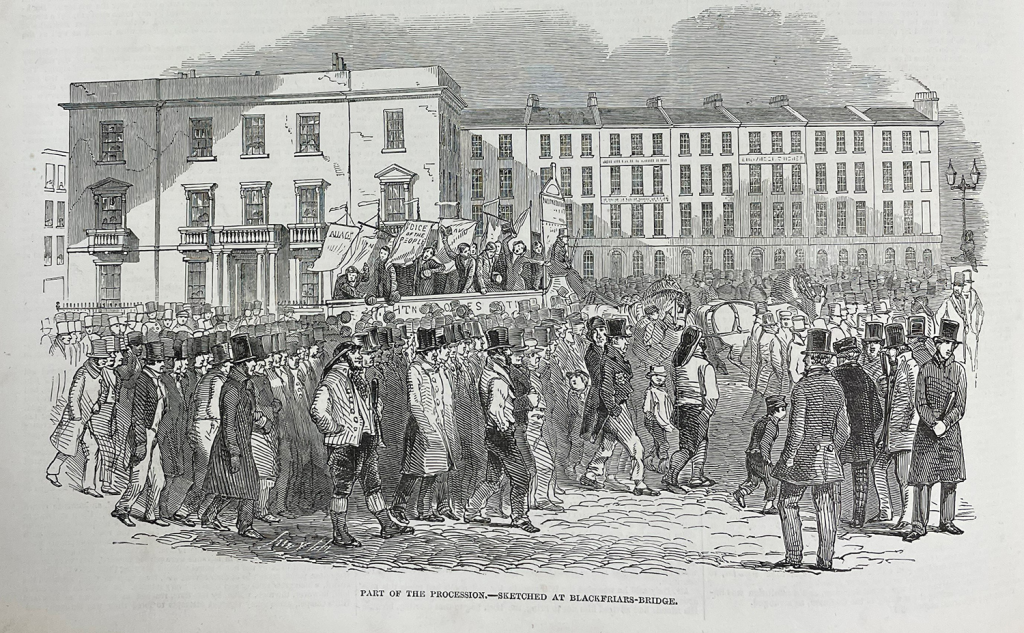

Chartism was a working class movement which emerged in 1836 in London. It expanded rapidly across the country and was most active between 1838 and 1848. The aim of the Chartists was to gain political rights and influence for the working classes. Their demands were widely publicized through their meetings and pamphlets. The movement got its name from the People’s Charter which listed its six main aims: annual elections for Parliament, a vote for all men (over 21), secret ballot, no property qualification to become an MP, payment for MPs and electoral districts of equal size.

In June 1839, the Chartists’ petition was presented to the House of Commons with over 1.25 million signatures. It was rejected by Parliament. This provoked unrest which was swiftly crushed by the authorities. A second petition was presented in May 1842, signed by over three million people but again it was rejected and further unrest and arrests followed. In April 1848 a third and final petition was presented. A mass meeting on Kennington Common in South London was organised by the Chartist movement leaders, the most influential being Feargus O’Connor, editor of ‘The Northern Star’, a weekly newspaper that promoted the Chartist cause. The third petition was also rejected but the anticipated unrest did not happen. Despite the Chartist leaders’ attempts to keep the movement alive, within a few years it was no longer a driving force for reform. However, the Chartists’ legacy was strong. By the 1850s Members of Parliament accepted that further reform was inevitable. Further Reform Acts were passed in 1867 and 1884. By 1918, five of the Chartists’ six demands had been achieved – only the stipulation that parliamentary elections be held every year was unfulfilled.

Universal Suffrage and Modern Democracy

From the late 18th century, some people advocated rights for women as citizens equal to that of men. Women played a part alongside men in general agitation for political reform in the early 19th century. The push for broader democracy continued into the 20th century. The Parliament Act 1911 limits the powers of the House of Lords by stating that money bills can become law if not passed without amendment by the Lords within one month and that the Lords cannot veto most bills but instead can only delay them for up to two years (or one month in the case of money bills).

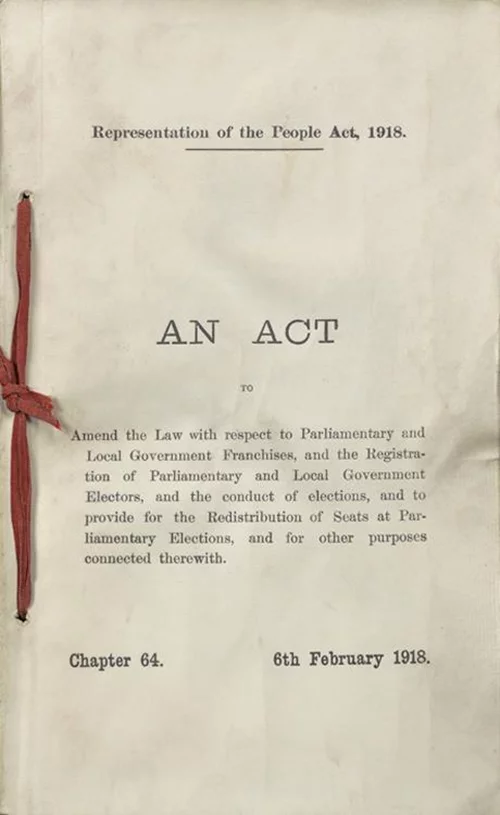

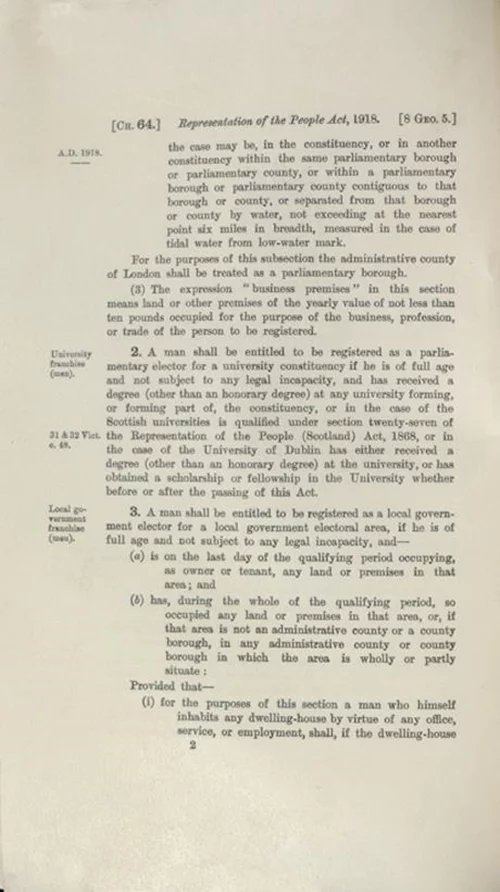

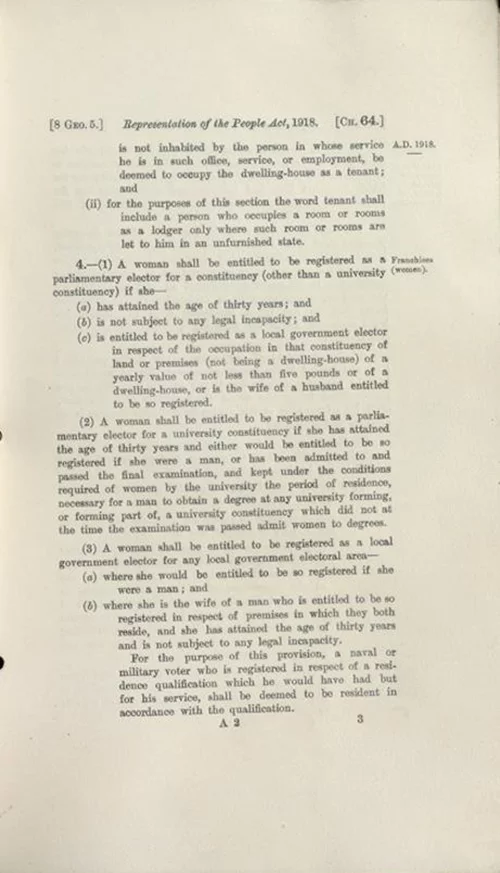

During 1916-1917, the House of Commons Speaker, James William Lowther, chaired a conference on electoral reform which recommended limited women’s suffrage. Only 58% of the adult male population was eligible to vote before 1918. An influential consideration, in addition to the suffrage movement and the growth of the Labour Party, was the fact that only men who had been resident in the country for 12 months prior to a general election were entitled to vote. This effectively disenfranchised a large number of troops who had been serving overseas in the war. With a general election imminent, politicians were persuaded to extend the vote to all men and some women at long last. The Representation of the People Act 1918 granted voting rights to most men over 21 and women over 30, followed by full equality in 1928. These reforms transformed the UK into a true representative democracy. The Labour Party emerged as a major force alongside the Conservatives, while the Liberals declined. The system stabilized into the constitutional monarchy and parliamentary framework we recognize today.

Suffragists and Suffragettes

Suffragist groups existed all over the country and under many different names but their aim was the same: to achieve the right to vote for women through constitutional, peaceful means. There were regional groups, especially in urban centres like Manchester, which held public meetings and petitioned at local level. At national level, key individuals included Millicent Fawcett and Lydia Becker. The suffragists believed in achieving change through parliamentary means and used lobbying techniques to persuade Members of Parliament sympathetic to their cause to raise the issue of women’s suffrage in debate on the floor of the House. Between 1870 and 1884 debates on women’s suffrage took place almost every year in Parliament. This succeeded in keeping the issue in the public eye as Parliamentary proceedings were extensively covered in the national and regional press of the time.

Suffragettes -The Pankhurst family is closely associated with the militant campaign for the vote. In 1903 Emmeline Pankhurst and others, frustrated by the lack of progress, decided more direct action was required and founded the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) with the motto ‘Deeds not words’. Emmeline Pankhurst (1858-1928) became involved in women’s suffrage in 1880. She was a founding member of the WSPU in 1903 and led it until it disbanded in 1918. Under her leadership the WSPU was a highly organised group and like other members she was imprisoned and went on hunger strike protests. Initially the WSPU’s tactics were to cause disruption and some civil disobedience, such as the ‘rush’ on Parliament in October 1908 when it encouraged the public to join them in an attempt to invade the House of Commons. 60,000 people gathered but the police cordon held fast. However the lack of Government action led the WSPU to undertake more violent acts, including attacks on property and law-breaking, which resulted in imprisonment and hunger strikes. These tactics attracted a great deal of attention to the campaign for votes for women. In 1910, a Conciliation Bill was read in Parliament. The bill was written to extend voting rights to women but failed to become law. Following its failure there were violent clashes outside Parliament. There were further Conciliation Bills proposed in subsequent years but they failed to resolve the situation.

How Politics Works in the UK Today

The UK is a constitutional monarchy with King Charles III as our current head of state in 2025, though his role is mostly ceremonial. Political power resides in Parliament, based at Westminster, comprising:

- House of Commons: 650 Members of Parliament (MPs) elected by constituencies.

- House of Lords: Unelected peers (currently around 800), including life peers, bishops, and hereditary peers, who review legislation.

- Government: Led by the Prime Minister, typically the leader of the majority party in the Commons, who forms a cabinet.

The Government introduces most plans for new laws, with many included in the King’s Speech at the opening of each session of Parliament, and changes to existing laws. However, new laws can originate from an MP or a Lord. Laws are proposed (bills), debated, and passed by both houses, then receive Royal Assent. Before proposals for laws, known as Bills, are introduced into Parliament, there is often consultation or discussion with interested parties such as professional bodies, voluntary organisations and pressure groups. The system operates without a single written constitution, relying instead on statutes, common law, and conventions. Some Bills apply to the whole of the UK. However, some may apply to one or more constituent parts – for example, only to England and Wales. Law-making powers in some subjects rest with the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh Assembly and the Northern Ireland Assembly, rather than the UK Parliament.

Voting in the UK

Elections are the cornerstone of UK democracy. In the UK, voting operates at different levels—local and national—each with distinct purposes, processes, and elected roles. Here’s how they work and differ:

Electoral System – Electoral Commission:

They are an independent body that oversees elections and regulates political finance in the UK. They aim to promote public confidence in the democratic process and ensure its integrity. They maintain the registers of political parties in Great Britain and Northern Ireland (Opens in new window). If a party wants to stand candidates at an election using a party name, description or emblem, they need to register. Their main responsibilities are:

- maintain registers of political parties in Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and register non-party campaigners

- provide guidance for anyone who might want to stand or campaign in an election

- publish political finance data

- regulate the imprint rules for parties and campaigners

- take action if they have reason to suspect the political finance law has been broken

- Find out more about how political parties are registered

Local Voting

Local elections in the UK involve choosing representatives for local government bodies, such as councils, which handle community-level services like waste collection, housing, local planning, and education. These elections occur in various parts of the country, typically every year in May, though not all areas vote annually due to differing election cycles.

Who’s Elected? – Councillors: These are elected to represent specific wards (small geographic areas) within a local authority, such as a city, borough, or county council. For example, London boroughs have councillors, while areas like Greater Manchester might also elect a metro mayor. Mayors: In some regions with devolved powers (e.g., London, Greater Manchester), voters elect a mayor to oversee broader regional issues like transport and economic development.

Voting System: Frequency: Cycles vary: some councils elect all members at once every four years, others elect a third of their members annually over a four-year cycle (excluding the fourth year). For instance, London borough elections happen every four years (next in 2026), while other areas might vote more frequently. Eligibility: UK, EU, and qualifying Commonwealth citizens over 18 who are registered to vote in the local area can participate. You vote based on your residential address. Turnout: Typically lower than national elections, often around 30-40%, reflecting less public focus on local issues.

National Voting

National elections in the UK primarily refer to General Elections, which determine the makeup of the UK Parliament in Westminster and, indirectly, the Prime Minister. They affect national policy on issues like taxation, healthcare (e.g., NHS funding), defence, and foreign affairs. General elections occur at least every five years (under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, repealed in 2022, returning to royal prerogative flexibility). The voting system is First-Past-the-Post (FPTP): each constituency elects one MP based on the highest vote count, historically favouring larger parties like the Conservatives and Labour. Citizens aged 18+ who are British, Irish, or qualifying Commonwealth residents can vote. Devolved governments in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland handle regional matters, elected via mixed systems (e.g., Additional Member System in Scotland).

Who’s Elected? – Members of Parliament (MPs): Each of the 650 constituencies across the UK elects one MP to represent them in the House of Commons. The party (or coalition) with the most MPs forms the government, and its leader becomes Prime Minister.

Voting System: General Elections use First-Past-The-Post (FPTP) exclusively. The candidate with the most votes in each constituency wins the seat, even without a majority. This can lead to a party winning government without a majority of the national popular vote (e.g., the Conservatives in 2019 won 43.6% of votes which secured 56% of seats and in 2024 Labour won 33.7% of the votes and secured 63.2% of seats). Frequency: Held at least every five years under the Fixed-term Parliaments Act (repealed in 2022), but they can occur sooner if the Prime Minister calls a snap election or if a no-confidence vote passes. The last General Election was on July 4, 2024; the next is due by mid-2029 unless called earlier. Eligibility: UK citizens, qualifying Commonwealth citizens, and Irish citizens over 18 registered to vote can participate, provided they reside in the UK (or are overseas voters registered within 15 years of leaving). Turnout: Higher than local elections, typically 60-70%, as national stakes (e.g., choosing the government) draws more attention.

Key Differences:

- Local voting affects immediate community services; national voting shapes country-wide laws and leadership.

- Local: Councillors and mayors; National: MPs (and indirectly, the government).

- Voting Systems: Both often use FPTP, but some local mayoral races use SV (With the Supplementary Vote, if no candidate gets over 50% of the vote, the top two candidates continue to a run-off and all other candidates are eliminated. When casting their ballot voters can put a second choice (who they would vote for in a runoff) on the original ballot paper), adding a slight twist.

- Local elections are more frequent and staggered; national ones are less predictable but less regular.

- Local results don’t directly influence national government, though they’re often seen as a barometer of public mood toward national parties.

Example in Context: On May 4, 2023, local elections saw Labour and the Liberal Democrats gain seats, hinting at discontent with the Conservative government—a trend that played out in the July 2024 General Election when Labour won a landslide. Yet a voter in, say, Bristol might back a Green councillor locally for environmental policies but choose Labour nationally for economic priorities, showing how local and national preferences can diverge.

Both systems rely heavily on FPTP, which critics argue distorts representation (e.g., smaller parties like the Greens struggle to win seats despite decent vote shares), but they serve distinct democratic purposes tailored to their scale.

Conclusion

The British political system evolved from feudal monarchy to a parliamentary democracy through centuries of conflict, reform, and adaptation. Its unwritten constitution and traditions make it unique, while its voting system ensures public participation, albeit with ongoing debates about FPTP’s fairness. This blend of history and modernity continues to shape UK governance in 2025.

Guides to Parliament – a series of free guides which you can read online

References & Links:

- Magna Carta – UK Parliament https://www.parliament.uk/magnacarta/

- Magna Carta – UK Parliament https://www.parliament.uk/magnacarta/#:~:text=Magna%20Carta%20was%20issued%20in,of%20Magna%20Carta%20(1215). – Magna Carta – British Library

- House of Commons Library – Magna Carta https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/magna-carta-does-it-still-matter/

- UK Parliament History of Parliament – UK Parliament

- Simon de Montfort https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/originsofparliament/birthofparliament/overview/simondemontfort/

- Britannica – Model Parliament https://www.britannica.com/topic/Model-Parliament

- History of the House of Lords https://www.parliament.uk/business/lords/lords-history/history-of-the-lords/

- National Army Museum The ‘Glorious Revolution’ https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/army-and-glorious-revolution

- GOV.UK Sir Robert Walpole (Whig, 1721-1742) History of government – https://history.blog.gov.uk/2014/11/20/sir-robert-walpole-whig-1721-1742/

- The National Archives: Reform Acts – National Archives

- The Chartist movement https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/chartists/overview/chartistmovement/

- UK Parliament Suffrage Timeline – UK Parliament

- How Parliament Works – UK Parliament

- Electoral System – Electoral Commission

- 2024 General Election Results https://election2024.electoral-reform.org.uk/