Abstract

The British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP) has recently unveiled its “Climate Change Guide 2025,” a compendium ostensibly designed to arm therapists with tools to combat “eco-distress”, a nebulous affliction purportedly arising from the existential dread of impending climatic apocalypse.

This article undertakes a rigorous, albeit tongue-in-cheek, academic evisceration of the guide, exposing its foundational assumptions as rooted in alarmist hyperbole rather than empirical sobriety. Drawing on critiques of climate catastrophism and psychological overreach, I aim to argue that the guide not only inflates minor worries into clinical syndromes but also risks iatrogenic harm by validating unfounded fears.

Through a section-by-section debunking, I reveal how this therapeutic zealotry transforms rational scepticism into pathology, all while ignoring the psychological toll of alarmism itself. Ultimately, I contend that true mental health resilience lies not in coddling eco-phantasms but in fostering critical thinking amid media-fuelled hysteria.

Climate Change Guide 2025 Nov 2025 – BABCP – Changing the Climate Conversation – A CBT approach to addressing the crisis

Introduction

In the grand theatre of modern psychology, where every fleeting emotion risks elevation to disorder status, the BABCP’s “Climate Change Guide 2025” emerges as a masterpiece of overreach. Penned by a cadre of well-intentioned clinicians, led by luminaries such as Dr. Steve Killick and Dr. Elizabeth Marks, the document posits climate change as an omnipresent spectre haunting the human psyche, manifesting as “eco-distress.”

This guide, crammed full of therapeutic recipes from Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) to Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), aims to “shepherd” sufferers through assessment, formulation, and intervention, all under the banner of addressing the “climate and ecological emergency.”

Yet, upon closer scrutiny, one discerns not a beacon of evidence-based practice but a house of cards built on shaky premises. The guide assumes, a priori (Knowledge acquired before or without experience), that climate change constitutes an unmitigated catastrophe warranting widespread psychological intervention, citing surveys like Hickman et al. (2021) to underscore youth anxiety over governmental inaction.

This overlooks the possibility that such distress stems not from environmental realities but from amplified narratives propagated by media and activists, narratives that, as critics argue, exacerbate mental health issues rather than reflect them.

Indeed, alarmism itself may be the true pathogen, contributing to rising adolescent anxiety and depression by painting a doom-laden future devoid of nuance or hope.

My thesis is straightforward: the BABCP guide, while cloaked in academic jargon, perpetuates insanity by medicalising adaptive responses to uncertainty, ignoring historical failures of apocalyptic predictions, and diverting therapeutic resources from genuine illness or disorders. I proceed by dismantling its sections, blending empirical rebuttals with a dash of cynical wit, to reveal the emperor’s new clothes, or rather, the therapist’s new billable hours!

Eco-Distress 1: Assessment & Eco-Distress 2: Formulation – Diagnosing Dread or Inventing Illness?

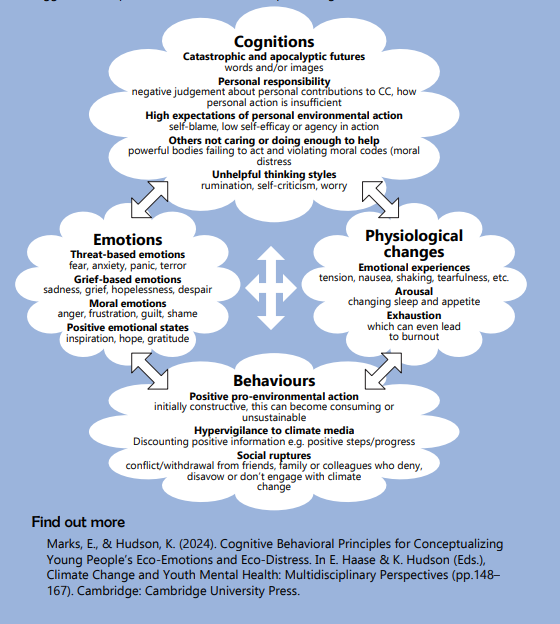

Dr. Elizabeth Marks’ contributions on assessment and formulation epitomise the guide’s penchant for pathologising the humdrum. Here, eco-distress is framed as a legitimate clinical entity, warranting tools like the “Mind over Mood” workbook to probe climate-related ruminations.

Marks invokes concepts like “environmental identity-based therapies,” suggesting clinicians assess distress through lenses of social justice and reflexivity, drawing on Burnham’s (2012) GRRRAAACCEEESSS framework, which, with its acronymic excess, already hints at overcomplication.

But: is eco-distress a pathology, or merely a rebranded form of generalised anxiety fuelled by sensationalism? Critics contend that labelling such concerns as “distress” risks creating self-fulfilling prophecies, where normal worries about weather patterns morph into therapy fodder. Moreover, the guide’s reliance on surveys like Hickman (2022) ignores how these instruments often capture transient emotions amplified by leading questions, not enduring mental illness.

Formulation, meanwhile, posits “positive tipping points” (Lenton et al., 2022) as counterbalances, yet this optimism clashes with the guide’s alarmist tone, akin to prescribing hope pills for a fabricated ailment.

Empirically, climate alarmism’s track record is riddled with debunked doomsdays: from Paul Ehrlich’s 1970s famine predictions to Al Gore’s ice-free Arctic by 2014, such prophecies have consistently faltered, suggesting that current eco-fears may be more media artifact than meteorological fact. By formulating distress around unverified cataclysms, the BABCP risks inducing the very anxiety it purports to cure, a classic case of psychological iatrogenesis.

The Ripple Effect and Exploring Ambivalence – Spreading Hysteria or Stirring Scepticism?

Dr. Killick’s “Ripple Effect” section imagines eco-distress as a cascading wave, impacting individuals, communities, and beyond, while his motivational interviewing approach seeks to resolve “ambivalence” toward pro-environmental actions. Citing Klonek et al. (2015), it employs techniques to nudge clients from denial to activism, framing scepticism as a barrier to be overcome!

But: is eco-distress a pathology, or merely a rebranded form of generalised anxiety fuelled by sensationalism? Critics contend that labelling such concerns as “distress” risks creating self-fulfilling prophecies, where normal worries about weather patterns morph into therapy fodder. Moreover, the guide’s reliance on surveys like Hickman (2022) ignores how these instruments often capture transient emotions amplified by leading questions, not enduring mental illness.

Formulation, meanwhile, posits “positive tipping points” (Lenton et al., 2022) as counterbalances, yet this optimism clashes with the guide’s alarmist tone, akin to prescribing hope pills for a fabricated ailment.

Empirically, climate alarmism’s track record is riddled with debunked doomsdays: from Paul Ehrlich’s 1970s famine predictions to Al Gore’s ice-free Arctic by 2014, such prophecies have consistently faltered, suggesting that current eco-fears may be more media artifact than meteorological fact. By formulating distress around unverified cataclysms, the BABCP risks inducing the very anxiety it purports to cure, a classic case of psychological iatrogenesis.

The Ripple Effect and Exploring Ambivalence – Spreading Hysteria or Stirring Scepticism?

Dr. Killick’s “Ripple Effect” section imagines eco-distress as a cascading wave, impacting individuals, communities, and beyond, while his motivational interviewing approach seeks to resolve “ambivalence” toward pro-environmental actions. Citing Klonek et al. (2015), it employs techniques to nudge clients from denial to activism, framing scepticism as a barrier to be overcome!

One might chuckle at the irony: in a field ostensibly committed to evidence, the guide treats climate doubt as pathological resistance, echoing Prochaska and DiClemente’s stages of change model repurposed for eco-conversion. Yet, psychological research on denial reveals it often stems from rational appraisals and more in-depth knowledge of conflicting data, not cognitive distortion. Critics of alarmism highlight how overstated claims, e.g., linking every storm to anthropogenic warming (environmental changes, pollution, or processes originating from human activity), erode trust, fostering “denial” as a sane response to hype.

Ambivalence, far from a flaw, might reflect prudent cost-benefit analysis: why upend lifestyles for marginal gains when models overestimate disasters? The guide’s ripple metaphor aptly describes its own potential harm, propagating unfounded fears that ripple into societal melancholy, as evidenced by studies linking alarmist messaging to youth depression. YES! They quoted Greta Thunberg!!

Acceptance in Dialectical Behaviour Therapy and Compassion Focused Therapy – Accepting Absurdity?

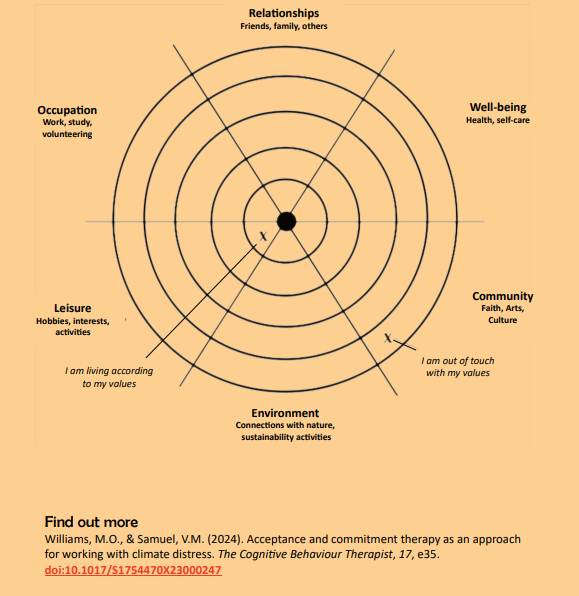

Catherine Parker’s DBT section advocates “acceptance” of eco-emotions, drawing on Linehan’s (1993) radical acceptance to tolerate distress without futile resistance. Similarly, Dr. Luis Calabria’s compassion-focused approach conceptualises eco-distress through self-kindness lenses.

Noble in theory, but applied to climate fears, this borders on absurdity: accept the “inevitable” apocalypse? Such fatalism mirrors the very doomsday narratives critiqued by sceptics, who argue that adaptation, not anguish, has historically mitigated environmental shifts. Compassion therapy, while soothing, risks validating pseudo crises; as one review notes, eco-anxiety correlates more with media exposure than actual impacts, suggesting therapy should debunk myths, not embrace them.

Nature-Informed CBT and Using Emotions Positively – Greenwashing Therapy?

Dr. Morwenna Roberts’ “Nature-Informed CBT” enthusiastically praises the virtues of spending time outdoors, citing outdoor exposure to boost wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours, citing Martin et al. (2020) on nature connectedness. Isabel Clarke’s section urges channelling emotions into climate engagement. While nature’s benefits are uncontroversial, tethering them to eco-distress smacks of greenwashing: prescribe forest baths for phantom fears? Critiques reveal that such interventions overlook how alarmism itself alienates people from rational environmentalism, turning stewardship into stress. Using positive emotions can feel empowering, but when it’s built on overblown threats, it becomes activism pretending to be therapy.

Additional Sections: From Children to Burnout – Infantilising the Intellect

The remaining sections of the BABCP guide, from addressing children’s responses to managing activist burnout and envisioning brighter futures, simply prolong the same core problems. They treat everyday worries as deep clinical issues, while quietly sidestepping the possibility that much of the distress comes from exaggerated, fear-heavy messaging rather than objective reality. Professor Catherine Malboeuf-Hurtubise’s contribution on using creative arts to explore climate change with children is a prime example. It encourages therapists to “make room for despair” in sessions, framing children’s emotional reactions to climate topics as something that needs special processing through art and philosophy. While creative expression can help children articulate their feelings, this approach risks turning normal curiosity or passing sadness into something more serious and permanent. By repeatedly exposing young minds to adult-level catastrophe narratives and then pathologising the resulting unease, it may unintentionally teach vulnerability instead of balanced perspective. Children absorb what adults emphasise; amplifying “despair” as a legitimate therapeutic focus could prime them for ongoing anxiety rather than resilience.

- Kamenetz, A., & Pikhala, P. (2023). The Climate Mental Health Wheel. Climate Mental Health Network. https://www.climatementalhealth.net/wheel

Dr Neil Frude’s “Levels of Conversation” section proposes structured ways to discuss climate issues at different depths, presumably to avoid overwhelming people. Yet this still assumes the topic is inherently distressing and requires careful handling, like tiptoeing around a fragile truth. In practice, it reinforces the idea that climate talk is emotionally loaded by default, potentially making casual scepticism or indifference feel like avoidance or denial.

- Ecological Systems Model (ESM) (Brofenbrenner, 2005), originally introduced by Urie Bronfenbrenner in the 1970s in the field of child development, can be used to think about our responses to climate change https://rotel.pressbooks.pub/whole-child/chapter/ecological-theory-2/

Claire Willsher’s piece on “living and working with eco-distress” draws from her own experience as a therapist and activist, describing personal struggles with the crisis. While honest, it blurs the line between professional help and personal activism. Therapists sharing their own climate journeys in this way may normalise intense emotional investment in apocalyptic views, turning therapy into a space that validates rather than questions those views.

Dr Rebecca Chasey’s section on addressing burnout and building resilience for people “acting on the climate crisis” targets activists specifically. It treats exhaustion as an almost inevitable by-product of noble commitment. This overlooks a simpler explanation: constant exposure to worst-case scenarios, endless urgency, and pressure to “do more” can wear anyone down, especially when the predicted catastrophes keep failing to materialise on the promised scale. Framing burnout as a badge of dedication ignores how alarmist narratives themselves drive the fatigue.

Finally, Dr Abigail Seabrook’s call to “reimagine a sustainable future” and move “beyond the crisis narrative” feels particularly ironic. The entire guide is steeped in crisis language, emergency declarations, ecological collapse, moral injury, so urging readers to shift away from doom feels like closing the stable door after the horse has bolted. True reimagining would start by questioning the crisis framing itself, rather than repackaging it with hopeful add-ons.

Taken together, these sections extend the guide’s pattern: they medicalise reasonable responses to uncertainty, treat activism fatigue as heroic sacrifice rather than potential over-investment in hype, and offer coping tools for problems partly created by the very alarmism being addressed. The result is less genuine mental health support and more reinforcement of a worldview that keeps people anxious, exhausted, and primed for endless therapeutic intervention.

Conclusion

The BABCP’s guide, while perhaps earnest, embodies the insanity of modern psychology’s expansionist tendencies: inflating climate concerns into a therapeutic empire.

By debunking its premises through alarmism critiques, I hope I have exposed how it perpetuates distress rather than alleviates it. True debunking demands redirecting efforts toward resilience-building sans hysteria, perhaps starting with a healthy dose of scepticism toward such guides themselves. In the end, the real emergency may be, or rather in my humble opinion IS the over-pathologisation of the human condition.

References

Zaremba, D., Kulesza, M., Herman, A. M., Marczak, M., Kossowski, B., Budziszewska, M., Michałowski, J. M., Klöckner, C. A., Marchewka, A. and Wierzba, M. (2022) ‘A wise person plants a tree a day before the end of the world: coping with the emotional experience of climate change in Poland’, Current Psychology, 43, pp. 12345–12356. doi:10.1007/s12144-022-03807-3.

Atkins, P. W. B., Wilson, D. S., Hayes, S. C. and Ryan, R. M. (2019) Prosocial: using evolutionary science to build productive, equitable, and collaborative groups. Oakland, CA: Context Press.

BABCP (2024) Climate and ecological emergency statement. [Online]. Available at: https://babcp.com/climate-and-ecological-emergency-statement/ (Accessed: 26 January 2026).

Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005) ‘Ecological systems theory (1992)’, in U. Bronfenbrenner (ed.) Making human beings human: bioecological perspectives on human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd, pp. 106–173.

Burnham, J. (2012) ‘Developments in social GRRRAAACCEEESSS: visible–invisible and voiced–unvoiced’, in B. Krause (ed.) Culture and reflexivity in systemic psychotherapy. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cohen, S. (2020) Eco-anxiety and other labels derail social activism, Cohen says. UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation. [Online]. Available at: https://luskin.ucla.edu/eco-anxiety-and-other-labels-derail-social-activism-cohen-says (Accessed: 26 January 2026). luskin.ucla.edu

Doherty, T., Artman, S., Homan, J., Keluskar, J. and White, K. E. (2024) ‘Environmental identity-based therapies for climate distress: applying cognitive behavioural approaches’, The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 17, e29. doi:10.1017/S1754470X24000278.

Freinacht, H. (2022) We must reclaim solarpunk from authoritarian regimes. Metamoderna. [Online]. Available at: https://metamoderna.org/we-must-reclaim-solarpunk-from-authoritarian-regimes/ (Accessed: 26 January 2026).

GOV.UK (n.d.) Climate change: applying all our health. [Online]. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/climate-change-applying-all-our-health (Accessed: 26 January 2026).

Greenberger, D. and Padesky, C. A. (2016) Mind over mood: change how you feel by changing the way you think. 2nd edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press (Original work published 1995).

Harris, R. (2019) ACT made simple: an easy-to-read primer on acceptance and commitment therapy. 2nd edn. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.Harsanyi, D. (2025) ‘3 apocalyptic climate change predictions that failed to come true’, Reason, 16 April. [Online]. Available at: https://reason.com/2025/04/16/3-apocalyptic-climate-change-predictions-that-failed-to-come-true (Accessed: 26 January 2026). reason.com

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A. and Lillis, J. (2006) ‘Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes’, Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), pp. 1–25.Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D. and Wilson, K. G. (2012) Acceptance and commitment therapy: the process and practice of mindful change. 2nd edn. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hickman, C. (2022) ‘Saving the other, saving the self: exploring children’s and young people’s feelings about the coronavirus, climate, and biodiversity crises’, in D. A. Vakoch and S. Mickey (eds) Eco-anxiety and planetary hope: experiencing the twin disasters of COVID-19 and climate change. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 77–85. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-08431-7_8.

Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R. E., Mayall, E. E., Wray, B., Mellor, C. and van Susteren, L. (2021) ‘Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey’, The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(12), e863–e873. doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(21)00278-3.

Kahneman, D. and Tversky, A. (1979) ‘Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk’, Econometrica, 47(2), pp. 263–292. doi:10.2307/1914185.

Kamenetz, A. and Pihkala, P. (2023) The climate mental health wheel. Climate Mental Health Network. [Online]. Available at: https://www.climatementalhealth.net/wheel (Accessed: 26 January 2026).

Klonek, F. E., Güntner, A. V., Lehmann-Willenbrock, N. and Kauffeld, S. (2015) ‘Using motivational interviewing to reduce threats in conversations about environmental behavior’, Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1015. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01015.

Lenton, T. M., Benson, S., Smith, T., Ewer, T., Lanel, V., Petykowski, E., Powell, T. W. R., Abrams, J. F., Blomsma, F. and Sharpe, S. (2022) ‘Operationalising positive tipping points towards global sustainability’, Global Sustainability, 5, e1. doi:10.1017/sus.2021.30.

Linehan, M. (1993) Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Linehan, M. (2015) DBT skills training manual. 2nd edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Macy, J. and Johnstone, C. (2012) Active hope: how to face the mess we’re in without going crazy. Novato, CA: New World Library.

Marks, E. and Hickman, C. (2023) ‘Eco-distress is not a pathology, but it still hurts’, Nature Mental Health, 1(6), pp. 379–380. doi:10.1038/s44220-023-00075-3.

Marks, E. and Hudson, K. (2024) ‘Cognitive behavioral principles for conceptualizing young people’s eco-emotions and eco-distress’, in E. Haase and K. Hudson (eds) Climate change and youth mental health: multidisciplinary perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 148–167.

Martin, L., White, M. P., Hunt, A., Richardson, M., Pahl, S. and Burt, J. (2020) ‘Nature contact, nature connectedness and associations with health, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours’, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 68, 101389. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101389.

Maslin, M. A. (2021) How to save our planet. London: Penguin UK.Mass, C. (2019) ‘Promoters of climate anxiety’, Cliff Mass Weather Blog, 9 December. [Online]. Available at: https://cliffmass.blogspot.com/2019/12/promoters-of-climate-anxiety.html (Accessed: 26 January 2026). cliffmass.blogspot.com

McCormack, L. (2025) ‘Climate anxiety as a form of sanity: Erich Fromm in the age of climate crisis’, Constellations, 32(3), pp. 1–15. doi:10.1111/1467-8675.70019. onlinelibrary.wiley.com

Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers (2019) Understanding motivational interviewing. MINT. [Online]. Available at: https://motivationalinterviewing.org/understanding-motivational-interviewing (Accessed: 26 January 2026).

Myers, J. (2019) ‘Wrong again: 50 years of failed eco-pocalyptic predictions’, Competitive Enterprise Institute, 18 September. [Online]. Available at: https://cei.org/blog/wrong-again-50-years-of-failed-eco-pocalyptic-predictions (Accessed: 26 January 2026). cei.org

Nature Matters in Mental Health (2024) Royal College of Psychiatrists. [Online]. Available at: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/news-and-features/blogs/detail/sustainability-blog/2024/03/06/nature-matters-in-mental-health (Accessed: 26 January 2026).

Newman, E. (2023) Imagining tomorrow podcast. Friends of the Earth. [Online]. Available at: https://friendsoftheearth.uk/about/imagining-tomorrow-podcast (Accessed: 26 January 2026).

Nguyen, P.-Y., Astell-Burt, T., Rahimi-Ardabili, H. and Feng, X. (2023) ‘Effect of nature prescriptions on cardiometabolic and mental health, and physical activity: a systematic review’, The Lancet Planetary Health, 7(4), e313–e328. doi:10.1016/s2542-5196(23)00025-6.

O’Donnell, D. (2024) ‘The end has been nigh for more than 50 years now’, MacIver Institute, 13 March. [Online]. Available at: https://www.maciverinstitute.com/perspectives/the-end-has-been-nigh-for-more-than-50-years-now (Accessed: 26 January 2026). maciverinstitute.com

Perry, M. J. (2022) ’18 spectacularly wrong predictions made around the time of the first Earth Day in 1970, expect more this year’, American Enterprise Institute, 21 April. [Online]. Available at: https://www.aei.org/carpe-diem/18-spectacularly-wrong-predictions-were-made-around-the-time-of-the-first-earth-day-in-1970-expect-more-this-year (Accessed: 26 January 2026). aei.org

Pielke, R. and Ritchie, J. (2021) ‘How climate scenarios lost touch with reality’, Issues in Science and Technology, 37(4). [Online]. Available at: https://issues.org/climate-change-scenarios-lost-touch-reality-pielke-ritchie (Accessed: 26 January 2026). issues.org

Pihkala, P. (2020) ‘Anxiety and the ecological crisis: an analysis of eco-anxiety and climate anxiety’, Sustainability, 12(19), 7836. doi:10.3390/su12197836. mdpi.com

Pihkala, P. (2022a) ‘Toward a taxonomy of climate emotions’, Frontiers in Climate, 3, 738154. doi:10.3389/fclim.2021.738154.

Pihkala, P. (2022b) ‘The process of eco-anxiety and ecological grief: a narrative review and a new proposal’, Sustainability, 14(24), 16628. doi:10.3390/su142416628.

Polk, K. L., Schoendorff, B., Webster, M. and Olaz, F. O. (2016) The essential guide to the ACT matrix. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Prochaska, J. O. and DiClemente, C. C. (1986) ‘Toward a comprehensive model of change’, in W. R. Miller and N. Heather (eds) Treating addictive behaviors. Applied Clinical Psychology, vol. 13. Boston, MA: Springer, pp. 3–27. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-2191-0_1.

Pyne, S. (2025) ‘Climate anxiety in pre-adolescent children’, Institute of Public Affairs, 30 May. [Online]. Available at: https://ipa.org.au/read/climate-anxiety-in-pre-adolescent-children (Accessed: 26 January 2026). ipa.org.au

Pyrah, S. (2023) ‘The nature cure: how time outdoors transforms our memory, imagination and logic’, The Guardian, 27 November. [Online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2023/nov/27/the-nature-cure-how-time-outdoors-transforms-our-memory-imagination-and-logic (Accessed: 26 January 2026).

Richardson, M. and Butler, C. W. (2022) The nature connection handbook: a guide for increasing people’s connection with nature. United Kingdom: Finding Nature Publishing.

Rogerson, M., Wood, C., Pretty, J., Schoenmakers, P., Bloomfield, D. and Barton, J. (2020) ‘Regular doses of nature: the efficacy of green exercise interventions for mental wellbeing’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1526. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051526.

Römer, J., Herrmann, A., Molkentin, K. and Müller, B. S. (2024) ‘Application of motivational interviewing in climate-sensitive health counselling – a workshop report’, Zeitschrift Für Evidenz Fortbildung Und Qualität Im Gesundheitswesen, 189, pp. 50–54. doi:10.1016/j.zefq.2024.07.003.

Seth, A., Maxwell, J., Dey, C., Le Feuvre, C. and Patrick, R. (2023) ‘Understanding and managing psychological distress due to climate change’, Australian Journal of General Practice, 52(5), pp. 263–268.

Shellenberger, M. (2019) ‘Why climate alarmism hurts us all’, Forbes, 4 December. [Online]. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaelshellenberger/2019/12/04/why-climate-alarmism-hurts-us-all (Accessed: 26 January 2026). forbes.com

Steentjes, K., Demski, C., Seabrook, A., Corner, A. and Pidgeon, N. (2020) British public perceptions of climate risk, adaptation options and resilience (RESiL RISK): topline findings of a GB survey conducted in October 2019. Cardiff: Cardiff University.

The Heritage Foundation (n.d.) Climate alarmism and the American family. [Online]. Available at: https://www.heritage.org/marriage-and-family/report/climate-alarmism-and-the-american-family (Accessed: 26 January 2026). heritage.org

The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act (2015). [Online]. Available at: https://futuregenerations.wales/discover/about-future-generations-commissioner/future-generations-act-2015/ (Accessed: 26 January 2026).

Thomashow, M. (1995) Ecological identity: becoming a reflective environmentalist. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.University of Derby (2018) Nature connectedness research group. [Online]. Available at: https://www.derby.ac.uk/research/themes/zero-carbon/zero-carbon-nbs-research-centre/nature-connectedness-research-group/ (Accessed: 26 January 2026).

U.S. Senate Environment and Public Works Committee (n.d.) Refuting 12 claims made by climate alarmists. [Online]. Available at: https://www.epw.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/4/a/4a86454f-4287-4d1c-ae5f-85a01b8c78b8/7E90482A76C15A7B2D2473E6EDC911C0.refuting-12-claims-made-by-climate-alarmists.pdf (Accessed: 26 January 2026). epw.senate.gov

Verlie, B. (2023) ‘Climate anxiety is not a mental health problem. But we should still treat it as one’, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 8 November. [Online]. Available at: https://thebulletin.org/premium/2023-11/climate-anxiety-is-not-a-mental-health-problem-but-we-should-still-treat-it-as-one (Accessed: 26 January 2026). thebulletin.org

Weinstein, N., Balmford, A., DeHaan, C. R., Gladwell, V., Bradbury, R. B. and Amano, T. (2015) ‘Seeing community for the trees: the links among contact with natural environments, community cohesion, and crime’, BioScience, 65(12), pp. 1141–1153. doi:10.1093/biosci/biv151.

Williams, M. O. and Samuel, V. M. (2024) ‘Acceptance and commitment therapy as an approach for working with climate distress’, The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 17, e35. doi:10.1017/S1754470X23000247.

Willsher, C. and Freeston, M. (2024) ‘My climate journey: one cognitive behavioural psychotherapist’s account, and a commentary linking to the scientific and practice literature’, The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 17, e28. doi:10.1017/S1754470X24000199.

Wilson, K. G. and DuFrene, T. (2008) Mindfulness for two: an acceptance and commitment therapy approach to mindfulness in psychotherapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Wullenkord, M. C., Tröger, J., Hamann, K. R. S., Loy, L. S. and Reese, G. (2021) ‘Anxiety and climate change: a validation of the climate anxiety scale in a German-speaking quota sample and an investigation of psychological correlates’, Climatic Change, 168(20). doi:10.1007/s10584-021-03234-6.